Teaching restraint in writing

This blog post is a few years old now (I think I first published it in 2011), so many things in my teaching have changed since them, however, this necessity for restraint in description is something that has never left my practice. So, enjoy…

What does good descriptive writing look like?

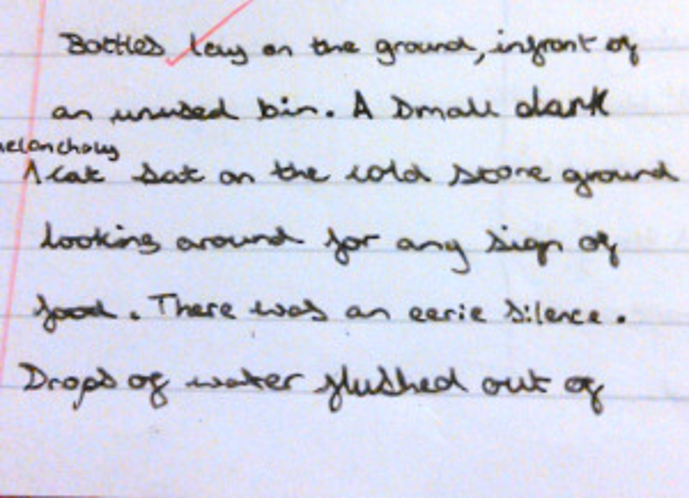

This was written by one of my year 7 students. It reads:

Bottles lay on the ground, in front of an unused bin. A small dark melancholy cat sat on the cold stone ground looking around for any sign of food. There was an eerie silence. Drops of water flushed out…

It continues in a similar vein for several paragraphs.

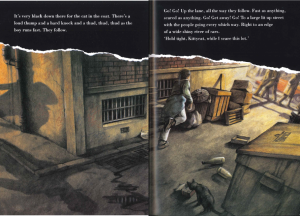

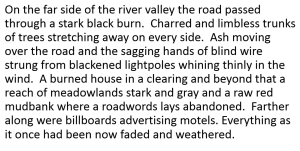

This is the picture the student was describing:

Many students believe that good writing is technique heavy. Perhaps because they don’t read widely, perhaps they don’t read regularly. So they are convinced that adjectives and adverbs are what’s needed. i want students to be able to write with subtlety and sub-text. They can learn when to withhold and when to run free.

Technique heavy?

If we layer technique upon technique, our writing can become cumbersome and over-embellished.

- When we being writing, we begin with simple sentences: The boy ran.

- We develop these to add visual imagery – The boy ran quickly.

- Later we add more precise adverbs – The boy ran sluggishly.

- Modifying adjectives and verbs: The overweight boy staggered painfully.

- We introduce different openers: Late again, the overweight boy staggered painfully onward.

- Vocabulary work adds: The corpulent man-child blunders unseeingly onward into the grimly lit darkening streets.

When I ask my pupils what good descriptive writing looks like – this is what they seem to think I want.

The curse of “show and don’t tell” has meant that pupils as writers are spoon-feeding their readers on a whole new level. Don’t show and don’t tell is perhaps a better maxim. (A side note on this – when we teach students techniques like ‘show and don’t tell’ remember they internalise language and I end up marking GCSE exam papers that read “The writer’s use of show and don’t tell suggests…) As I said, don’t show and don’t tell is sometimes better.

On becoming writers who read

The literature that we study at school is only worthy of study because we have to study it. The reader’s interaction with the language of text – gleaning meaning where it is hidden, is what we do when we analyse. It’s not easy to write an essay paragraph using the quote “He slammed the fork down angrily” as there is nothing to infer. The writer has set it out for us.

When we teach pupils that they must create such a vivid image for the reader and that they must include as much detail as possible. Then we leave our readers with no work to do. Often their writing is filled with subjective emotional language, but by placing this into the text, they have robbed the reader of their own reaction.

Writing as detectives

I am teaching a scheme of work studying Mystery and next week we are due to start reading Poe’s Murders in the Rue Morgue. In order to get into the mystery swing of things – this week I wanted pupils to pare back their writing, by writing description as detectives.

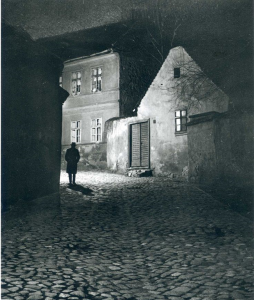

The lesson began with this extract from The Road by Cormac McCarthy (*klaxon* you might not want to use this text with every class!)

As detectives, pupils identified all the nouns and then explained what exactly was being described. I then asked them to remove all the grammatical words to force their focus on to the nouns and noun phrases. Finally we identified the adjectives.

By focusing on the nouns – students were more able to understand the ‘mystery’ in this extract. It almost sounds counter-intuitive but this literal description allows for detailed inference – “the sagging hands”.

Scientific, observational description

Students had to explain this forensic, scientific approach to writing, that did not use any emotional, subjective language. They described McCarthy’s landscape as realistic or ‘true’ as the students named it.

This image then required a detective’s eye to describe. We started with nouns – precise and detailed.

A few we listed were:

– a man, wearing an overcoat and hat

– a shuttered door

– four windows with six panes

– a building with high eves

Next I asked pupils to describe these nouns in the most scientific way possible and I asked why the sentence below is not forensic.

The shadowy, mysterious path went up to the crumbly, ancient building.

It was this part of the lesson that resulted in the most discussion and debate among students.

“You can’t use ‘eerie’ since when would a detective say it was ‘eerie’?”

“Gloomy is out – right Miss?”

“How can I say the building is old without exaggerating, it’s not ancient.”

By giving students the vocabulary ‘subjective’ and ’emotional’ they were able to critique their own ideas. Often writing down and then removing words that were considered to be weak.

The final 15 minutes of the lesson was spent writing just 10 sentences of scientific description. Here are some of their attempts:

- “Walking towards the light, a man alone digs his hands into the pockets of a long overcoat.”

- “Stretching away to the left, the uneven cobbles absorb the black and grey of night.”

- “Four, six paned windows reflect the streetlight exaggerating the darkness beyond”

- “Darkness to the left and to the right. Light cuts threw the centre”

On the face of it, this ability to show restraint in writing allows students to write in a manner that is more ‘true’.

Subjectively, I think this writing is closer to ‘good writing’ than writing that is created via a checklist of word types, sentence types, and techniques. It would certainly uphold more analytical scrutiny.