- in British Literature , Macbeth , Shakespeare

Macbeth: 3 ways to take your lessons to the next level!

As we get towards September, I know teaching Macbeth is just around the corner. Again. Please don’t misread me, I LOVE teaching Macbeth. It’s almost my favourite Shakespeare play to teach (see my post on teaching The Tempest).

I teach Macbeth every year and every year I find I l-o-v-e it all over again! In my class, there is no room for a quick trot through the play. My students all sit an examination on the play at the end of their 2 year English Literature qualification. We have to know the play and know it very well. Each year I try to add something new to my Macbeth armoury.

Here are 3 ideas that I used this year to take my teaching of Macbeth to the next level!

1. Get stuck into Holinshed’s History

Raphael Holinshed was an English chronicler (similar to a historian today) and it is his chronicle of English history that was Shakespeare’s main source for the play Macbeth. Holinshed published two ‘complete histories of England, Scotland, and Ireland’ in the years 1577 and 1587. Each publication holds a large and comprehensive description of the history of these three nations.

Holinshed’s version of the story of Macbeth describes the reign of King Duncan and shows Macbeth to be a bloody dictator. It also included a woodcut illustration of the three witches that presents them more as nymphs or fairies, and less like the dark, genderless creatures in Shakespeare’s play. You can find out more about Holinshed and his chronicles here at the British Library site.

I have included resources for Holinshed’s history in my Macbeth unit on TpT. If you’re curious about what’s included you can find it here!

How do I use Holinshed in the classroom?

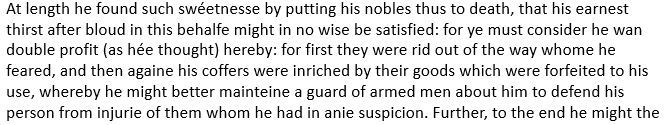

It is very simple, we have a short extract that we read directly from Holinshed (like the one below). We read it directly in Early Modern English (Elizabethan English) – you can talk to students, if you feel like it, about this transition moment in the English language. I love that Holinshed, like Shakespeare, shows both the old styles and new styles in his writing.

So somewhere around the end of Act 4 and the beginning of Act 5, we read a page from Holinshed, describing Macbeth’s later reign (remember Macbeth was actually King of Scotland for 17 years). We chuckle at the funny spelling and words.

Then we talk about the differences between Holinshed’s description of Macbeth and Shakespeare’s one. Holinshed generally comes out the winner because his presentation of Macbeth is bloodthirsty to the extreme.

After that, I ask my students to discuss the play by referencing Holinshed’s history. I might use sentence starters like:

- Holinshed’s Histories reveals Macbeth castle at Dunsinane was…

- Holinshed explains the complete nature of Macbeth’s tyranny…

2. Explore 1606

The year that Shakespeare wrote Macbeth was a truly spectacular year for English culture and politics. Not only did London see the first performances of King Lear, Macbeth, and Antony & Cleopatra in that one year but England was rocked, almost constantly by political intrigue.

Let’s start with the obvious:

- In late 1605 the Gunpowder Plot saw a failed assassination plot to kill the King. Let me say that again – kill the King. Now, according to medieval beliefs, the King is God’s representative on earth. A man appointed by King to rule of the earth.

- To kill the king (I love the word ‘regicide’) was then to kill God’s appointed leader, to go against God’s plan, and to break his organisation and order of all the things. To kill the king was to go against nature himself.

- Now many of us know the Gunpowder Plot because of Guy Fawkes and 5th November and fireworks night. But, what is often overlooked in our popular memory of history is that the Gunpowder Plot was arranged by a group of Jesuit priests.

- In fact, the assassination plan was known to the head Jesuit priest in all of England, Henry Garnet. So let’s recap: a group of priests were planning to kill God’s representative on the throne. Wow! Something surely was rotten in the state of Denmark (I mean England).

- The sensational trial and execution of Henry Garnet, Guy Fawkes, and other members of the Gunpowder Plot took place in early 1606.

- Think back to Macbeth – what happens? That’s right. The King is murdered. Right in front of the audience, Shakespeare plays out the ‘what might have been’. It’s like Shakespeare invent reality TV 400 years before Big Brother.

- Added that we have the Berwick Witch trials, the Oaths of Allegiance to the King, Catholic Equivocation, James’ own version of the Inquisitions, and…the hint that Shakespeare might have been a Catholic sympathiser. Well, it seems, 1606 was a year of intrigue.

3. Get stuck into Shakespeare’s sounds

I have a long post already about how I teach Shakespeare meter and rhythm. You can read it here. I use many of the same strategies when I teach Macbeth, but I can never pass up the opportunity to add a little piece to my metrical teaching.

Here are a few ideas that I love in Macbeth:

- Most of us are happy with Shakespeare’s basic metrical rhythm, iambic pentameter. Here’s an example from Act 5. But get thee back; my soul is too much charged. You can see the “iamb” which is the pattern of ‘unstressed’ then ‘unstressed’ syllables. Then the pentameter is 5 pairs of syllables. So 10 syllables per line.

- A “trochee” is the opposite of an “iamb”. This is where you start with the ‘stressed’ syllable and it followed by an ‘unstressed’ syllable. Because the stressed syllable comes first, the trochiac meters tend to sound harsher. Gall of goat is a great example from the witches’ spell Act 4 Sc 1. Many characters move to speaking in trochiac meter at different points in the play. The break in the usual meter shows emotion, turmoil, or change.

- The witches don’t just invert the metrical pattern, they also use a lesser number of syllables. This is called catalexis. The process by which a metrical pattern is cut short for effect (it can be at the beginning or the end). Shakespeare doesn’t just give the witches otherworldly words to say, he gives them a whole otherworldly way of speaking.

- Their lines are shorter than the other characters’ lines – often made up of seven syllables (seven was associated with witchcraft). Consider the symbolism of this, they have short lines because Shakespeare shows they are less than human.

- Their chants are mostly written in a catalectic (incomplete) form of trochaic tetrameter, which sounds like an incantation or magical spell.

If you’re curious to learn more about how to teach the meter and sound patterns in Shakespeare then do read my other blog post and download the free resource.

You can also see my complete Macbeth unit by clicking on the picture below:

Finally if you would like to receive free Literature and Writing teaching ideas straight to your inbox, then sign up below!

Subscribe to my weekly teaching tips email!

Sign up below to receive regular emails from me jammed packed with ELA teaching tips, tricks and free resources. Also access my free resource library!