Category Archives for "Literature"

Teaching A Level English Literature is one of the real privileges of my job, I absolutely love teaching it – I love the texts, the setup, as well as the discussions and debates I have with my classes.

In late-March when English schools closed for onsite lessons, teachers were thrown into the world of digital learning. For me, this was new and a little scary!

I was faced with teaching half of The Handmaid’s Tale remotely.

How was I going to get my class through the reading?

How were we going to tackle the big questions?

And the small details?

How were we going to debate and discuss the events and ideas?

It became apparent early on that, despite my natural tendencies, I needed to give my classes more, extra, above what I would usually, to help them navigate the new and bizarre world of learning at home.

Our A Level Literature classes are truly mixed ability, we accept students with a passion for reading onto the course and don’t worry too much about outcomes on enrolment.

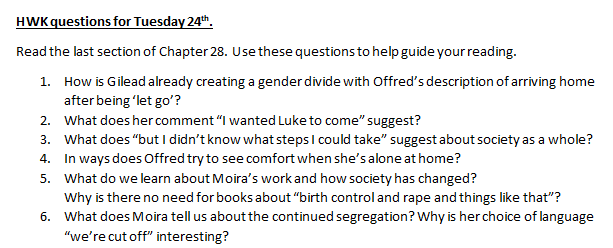

So setting an endless series of questions to guide pupils through reading was not a good idea. You can see here from 24 March (first week of lockdown), my work set could have been overwhelming, especially if it stayed in this form for 3 months. And understandably so.

My students were used to:

Guidance and explanation from an expert

Bouncing ideas off each other and clarifying their own thoughts through dialogue

Adding to each other’s ideas and challenging them

They weren’t used to reading, thinking, and answering in a void.

I just want to pause here and say something about the idea of independence in education. Creating independent learners is seen as something of a panacea in education circles. The constant drive towards independent thinking and independent working can miss the point.

Children need teaching. They are sponges for knowledge and knowledge doesn’t come out of a vacuum.

You might think that The Handmaid’s Tale would be an ‘easy’ text to teach remotely. After all, it’s not laborious 19th-century prose. It deals with contemporary themes. It’s engaging to read.

Well, if you think that, you’d be wrong. There’s a reason why it’s an A-Level text and isn’t because it’s an easy read.

A thorough and wide-ranging knowledge of global history.

A good understanding of post-war social history in America, and in particular an in-depth understanding of Christian Right. This needs to go way beyond a basic understanding of evangelicalism and into how traditional Christianity reshapes individual identity and culture.

Speaking of Christianity – you need a pretty good understanding of Old Testament tradition and writings. Atwood uses the Bible verbatim, she uses passages and alters just a handful of words, she uses passages out of context – all as part of her creation of Gilead’s ideology.

Atwood is a master of language. Her wordplay and multiple layers of meaning created by her words choices and images require careful thought to unpick.

The level of general knowledge needed to interpret the text is enormous (lingerie parties, medicine, the environment, and geopolitics to name just a few). This doesn’t even take into account the numerous details in the Historical Notes.

The novel is full of postmodern strategies, these are tough to explore all by yourself.

Ok, so you get the point. I couldn’t just send work to my class and expect them to get it. No matter how good my questions were.

My school aren’t running live video lessons, for safeguarding reasons (that I completely agree with). I needed a plan that would do more.

First up – fun, yes they are A-Level students. But they are also kids. So we decided that having fun during lockdown was totally acceptable. Here is my contribution to our Loo Roll Literature challenge

If we were studying The Handmaid’s Tale in normal times, we would have been reading the novel and talking about it during lessons.

So that’s what we’ve been doing.

I made videos of me reading and discussing the language and context which I asked my class to watch. I got better as time went on – but at first, I was super uncool at it. Lolz.

Then we discussed each chapter using the chat function in Microsoft Teams. I would write 5/6 discussion questions for each chapter and would stick them on Teams. We worked asynchronously, so my class just added their comments to the question threads when they had time.

Some areas need further discussion and explanation. So this is what I did.

Not only are these useful for my students as they study, but these lessons are now there forever. They can come back to them as they revise. I can use them again in the future.

I know I said independence isn’t the only end goal, but that not to say that we should help students make steps towards it. We set independent study tasks each week. They are clear, focussed, and have a defined outcome. This is far more effective than asking students to “read a chapter of the novel and make notes on it”.

Teaching academic essay writing when pupils are sitting in front of you is difficult. How much help is too much at A-Level? Some students need carefully differentiated support for essay writing. Some arrive in our classroom with their academic voice fully developed.

So I took a one-size-fits-plus approach. Whole class input on essay planning and writing. Then lots of personal, 1-2-1 feedback and advice on essay plans, introductions, etc.

My students are now writing their comparative essays and I hope they feel as confident as they would in my classroom.

Next week move onto the coursework unit and interestingly, independence is the name of the game.

Several years ago I participated in a piece of classroom research into how essay writing is taught in English. It was a honour for me to add my voice to this conversation. Before the 2015 specification, the keys to success in exams for essay writing appeared to be about reduction and concision, rather than detail and breadth. There was one year when some students were encouraged to draw a PEE table onto the exam paper!

The conversation has moved on a great deal in the intervening years. The voices in Team English had add some fantastic alternatives. If you are looking to develop your teaching of essay writing, then a fantastic first point of call is Becky Wood’s (@shadylady222) blog Why I No Longer PEE.

If you are interested in reading my NATE article on PEE – then you’re in luck. They have very kindly agreed for me to share it here. So thank you NATE – while I am on the topic, do have a look at their website.

So here is my article. Just click on the image below to read the whole thing.

I love using short films in my classroom. I bet you already have a collection that you like to you. I’m not different. I use short films for a bunch of different reasons: to introduce a new idea, or to explain something we all found complicated. Sometimes to inspire discussion and debate, or to get stuck into some creative writing. Short films are fabulous for both literature and writing.

So, here are my top 5 favorite films for high school ELA. I’ve split them so you have:

I love using this short reading of the children’s classic, The Tiger Who Came to Tea, with my older literature classes. In fact, I used to only use with my senior students who are studying literature and needing to apply different critical theories. Over the last few years, I have been using it as a debate prompt with my younger students as well.

The first question I ask is “what does this text tell us about society?”.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eob3MtLkgK0

At this point, I introduce critical theory. Gender and feminist theory and also Marxist theory. *Warning* – this discussion does result in some criticism of Judith Kerr’s text. It’s great to consider the narratives that shape our understanding of the world as children, but it’s not always a comfortable discussion.

We discuss:

At this point, I might draw a comparison between this text and invading forces: the Nazis in Poland, Judith Kerr has spoken of this being the inspiration for her story. The discussion is often lively.

An interesting counterpoint to this story is the another children’s story – Where the Wild Things Are. Here we develop our discussion to include colonization, imperialism, and how other races and ‘the foreigner’ can be represented in literature.

Again the discussion is often lively.

Copy Shop is an unusual silent film by Virgil Widrich, 2001. It received an Oscar nomination for a short action film. The film is 12 minutes long and ‘tells’ the story of a man who accidentally photocopies himself until ‘he’ takes over his town.

Just this concept alone is intriguing enough for students!

I often begin this lesson by asking students to mind-map all of their thoughts on the topics of:

These thoughts can be as generic or as specific at you decide. I generally put these topics on the board and then pose the question “write down everything that comes into your mind”.

After watching the film, sometimes twice, I ask students to add ideas to their mind-maps based on the film. For identity and society – we discuss how we are shaped as individuals, how society shapes us into a particular mould. For gender and relationships – students often notice that the single female is replaced by the male, that the relationships show companionship, then threat. For reality – we discuss to what extent we can trust our senses, what we see.

The final step is to debate some of the big ideas in literature:

I could go on!

I use this short and sad story for a variety of different reasons with my classes: writing flashbacks, relationships, realistic dialogue, incidents, and memory writing.

It’s a poignant tale and dedicated to survivors of Leukaemia, a sensitive one to use with classes but often generates excellent sympathetic debate and great emotionally intelligent writing.

*Warning* – this short film is the epitome of suspense and then a moment of terror. Your class will scream. Please, please, please watch through till the very end before you decide to use it! Don’t look away at the end, otherwise you might miss ‘it’! To be absolutely clear – you get a glimpse, the most fleeting glimpse of ‘it’.

Ok, you survived! Here’s how I use this film: to build tension, to create a character who has no idea what is about to happen next.

This short film is fantastic for writing a realistic moment of suspense – rather than one that is filled of creaky staircases and slamming doors. Write a character who has literally no idea what is about to happen to them!

You need to be speedy with the pause button here. I watch with kids up to the bit where the man collects his keys. Then pause. We write this opening section as descriptive narrative.

Then we watch – pause – write until the very end. As the students haven’t seen the whole thing – when they first see the figure – they are shocked, their character can be shocked. So their writing is often much more authentic, than if we had planned it in advance.

It’s great for writing genuine expressions of a character’s experience of cluelessness to horror.

Another one from the guys at the Jubilee Project, I do love them, and to be honest you could use any of their films effectively in the classroom.

But Fireflies is something special.

I pose a bunch of questions when using this film, sometimes before, sometimes after, sometimes both!

This short film is actually an extended advertisment for the outdoor clothing company Patagonia. Sean Villanueva O’Driscoll is on the road talking about climbing and about his very patched and repaired jacket. It’s such a beautiful film and would be great as a writing prompt. Here it is “The Stories We Wear by Patagonia”.

These British 100-year-olds talk about their lives, their experiences, and they dispense advice about how to be happy. Sit back and prepare to get emotional! Find it here “life lesson from a 100-year-old”

As this is a classic English Literature GCSE text, I cannot resist this Jekyll and Hyde song. Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde…when a good man releases his evil side…Mr Hyde and Dr Jekyll…who are the characters when the dust settles? 🙂

Enjoy all the chuckles here “Jekyll and Hyde characters song”

Alma is such a great short cartoon, it’s absolutely perfect for creative writing. It is silent, sinister, and completely mesmerizing. Watch Alma here

I promise to keep adding to these as I find them, but do drop your favorites in the comments below!

While you are here, please do consider signing up to receive my weekly creative writing email, titled Writing on Wednesday. Every Wednesday, I email out my teacher-friends a writing prompt or some writing advice.

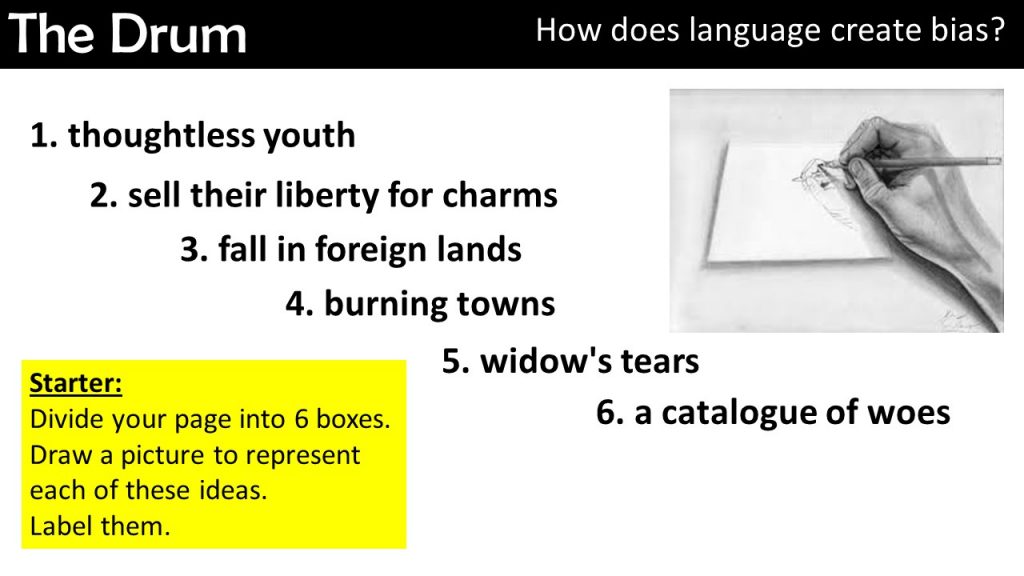

Helping students engage with and understand literature before they read is essential. One way to take the fear away from old-fashioned language or writing that is unfamiliar is to let students play with it before you read.

This pre-reading activity is deceptively simple. Here’s what you do:

It always amazes me how varied, interesting, and deep my students’ interpretations of these words are. Remember they have no idea what they are going to be reading. Yet students are able to see the depth in the language so much more easily when they only have a handful of words to deal with.

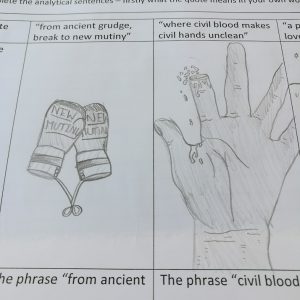

Here are a few examples of my student’s work: from Romeo and Juliet and the task above on The Drum!

If you try using this activity with your class, drop me a note in the comments to let me know how it went! You can see all my Literature resources here.

Sign up below to receive regular emails from me jammed packed with ELA teaching tips, tricks and free resources. Also access my free resource library!

If you are looking for new and creative ways to embed ‘character’ into your curriculum, then this post is for you! In this video, I share 2 ways you can use character in your ELA classroom. Firstly, in creative writing and secondly, in your study of literature.

So enjoy!

And then checkout this >>>DOWNLOAD<<< to help you on your way!

*I send emails with teaching tips, tricks, and free resources to my subscribers regularly. I value your privacy and you can learn more about how I handle your data in our private policy. You can unsubscribe at any time.

Love British Literature?

Access this Austen free resource and a whole lot more!

If you are ready to bring a bit of Brit Lit spark to your classroom - then this Austen resource pack is for you!

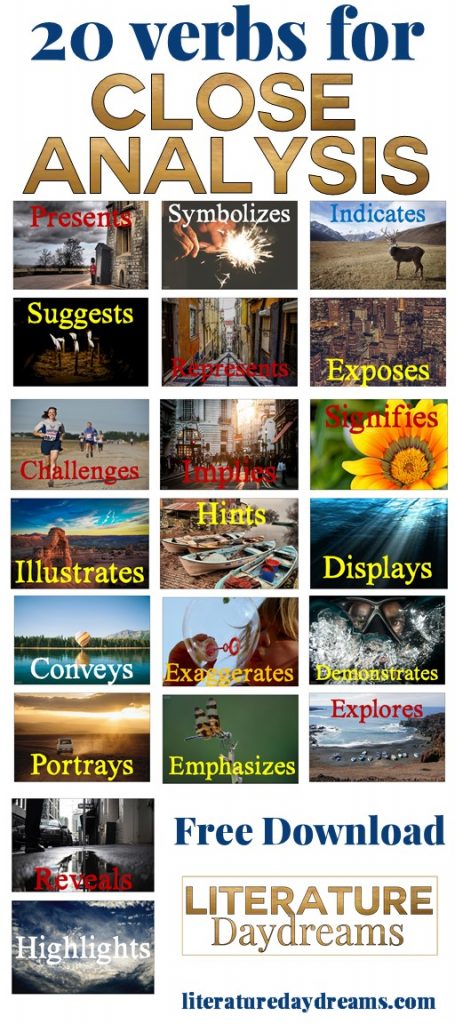

In my classroom, we spend a great deal of time analyzing language and techniques in literature. Often one we have read and discussed a text, my students are confident with their ideas. They have things to say about the language used, the structure, or the form. Yet they can struggle to put these ideas to paper.

I avoid using sentence frames for literature essay writing whenever I can. They are hugely restrictive and it is boring to mark a whole set of essays that read the same.

One way to improve how close analysis is written up is to focus on the verbs of analysis. I have these 20 posters up in my classroom and I refer to them frequently. I also have them printed in a small task card size so students can have them on their desks.

These verbs not only help students focus their thinking and ideas, but also allow them to bring some variety to their analytical writing. We are avoiding the overuse of ‘this suggests’ and ‘this implies’!

This list of 20 verbs is free for you to download here!

While you are here – consider signing up for my weekly newsletter. Every Sunday I send out two teaching ideas: one classroom activity, and one literature activity. You can sign up using the form below!

Sign up below to receive regular emails from me jammed packed with ELA teaching tips, tricks and free resources. Also access my free resource library!

We all love a period drama don’t we? Well, you and I probably do. But your average teenager… Reading 19th century literature with classes presents us, as teachers, with a number of unique opportunities. It is at this moment that we are, probably, at our most multi-disciplinary. We are scientists – discovering electricity and inventing CPR. We are adventurers – seeking out the south pole and charting the North West Passage. We are theologians – struggling to believe in the Age of Enlightenment. We are historians – obsessed with the Classical Age, avoiding the present. We are politicians – fearing Revolution and rebellion. When I look at the 19th Century I see all the “old England” of smugglers, pirates, and highwayman and I also see all the “new England” of the factories, technology, and workhouses.

1. Starting at the beginning

1. Starting at the beginningBefore I even put a piece of 19th century literature in front of my students, I pose the question: “What is the difference between life today and life in 19th century?”. Generally, at first strike – I get only the obvious answers (people were dirty). The knowledge that my students have of history is limited. They can tell me loads about life in the workhouse, they can talk about factories. But beyond these specifics they are still in the dark. “History” says the historical novelist Dame Hilary Mantel “is what’s left in the sieve when the centuries have run through it”. The bits we pick out of the sieve to teach our younger students is pretty specific.

So what are the main differences we see:

Once we have made this list, it’s time to jump straight in and look at some writers. At this point – I might set my classes up with an author research study. Sometimes I find it is favourable for students to know in advance some of the historical and biographical details linked to a particular author. For Austen, Dickens, and Shelley, these are particular relevant.

We also tend to notice that while there are few narrative links between stories we read (A Christmas Carol -> Pride and Prejudice -> Frankenstein); we do come across the same ideas again and again. The abuse of power, the issues of social class, the treatment of the poor, the role of women in society. Each of these novels, in some way, speaks to these universal themes again and again.

Ok, so we’ve talked about the differences between now and then, we’ve met the author. We can’t put off reading the text any longer!

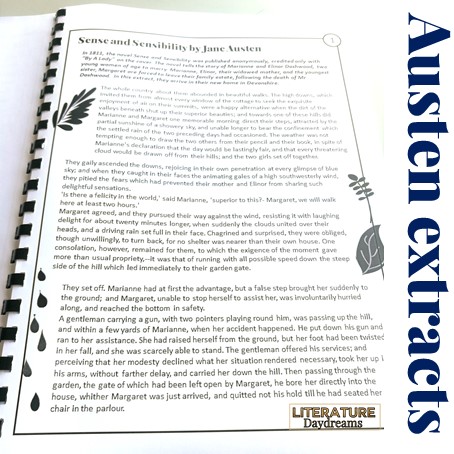

We also don’t always read full texts (shhhh don’t tell the writers!). There are some 19th century texts that our national curriculum and examination syllabi require us to study. But other than that we have free reign. However, given that many are 300+ pages and some have opening sentences that run to 100+ words, I don’t always decide to read entire novel. In fact this year, I have been teaching extracts only. Extracts from my favourite 19th century fiction and I have been BLOWN AWAY by the understanding shown by my students. This broad range has given them a far greater insight into this area of British Literature than if we had just focussed on one novel. The image above shows an extract from Sense and Sensibility that we love to study!

There are 5 skill areas that I cover when we read 19th century literature:

Developing comprehension of these extracts can take time. I don’t want to tell students what everything means, being reliant on the teacher in that way doesn’t help anyone. But – students need to know a whole bunch of stuff before they can even begin to grapple with the ideas and points of view presented in a text. For example: the language here is quite tricky. Marianne states “Is there a felicity in the world superior to this?” I kid you not when I ask classes about this sentence – they often think it is about a girl named Felicity. When we are reading we are trying to work out what is going and what can sometimes be hindered by our understanding of language. So comprehension of narrative and comprehension of language must go hand in hand.

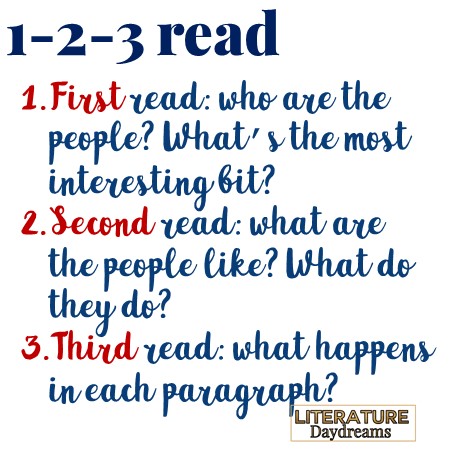

Students are great at creating a general understanding of what is going on by themselves. They know that they won’t get it all straight away. So we do a 1-2-3 reading strategy.

I start off by reminding students that a 500 word extract should only take about 2.5 minutes to read. I tell them, that because I love them and because it’s like “way old writing”, I’ll give them 3 minutes.

And what do you find? That despite not knowing what the word ‘felicity’ means – students have understood what happens in each paragraph. This particular extract from Sense and Sensibility is perfect for this exercise (and guess what – shhh – you can download it as a freebie here).

So now we know what is going on in the extract – we can flip back and do some word work. This is absolutely vital before we do any close analysis. It would be very easy to treat this as another dictionary task, but one issue with 19th century literature is the use of language that has slipped outside of everyday usage. Students need to grapple with these words for themselves before they can interpret another writer’s use.

For me then this word work is 2 phrase: first the dictionary work to define and then second to use these new words (or reframed words) in their own writing. The examples above are sentence starters that I give students using the vocabulary. I do this because with this students are more likely to use language correctly with this additional support, than if asked to just come up with their own idea.

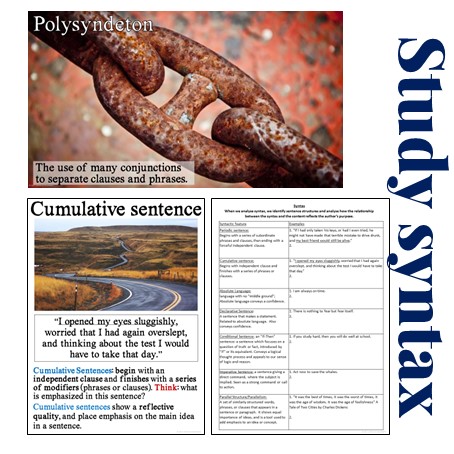

The final area we really focus on when studying 19th century literature is syntax and sentence structure. For us in the modern age, the event of modernism, saw a revolution in sentence structure. Authors rejected the highly embellished writing of their predecessors. Modern writers use shorter sentences and fewer clauses. Students can find reading the long sentence types seen in 19th century literature a challenge. So I turn it into a puzzle or a scavenger hunt.

By teaching the syntactical structures, such as polysyndeton, cumulative, and periodic sentences, students can make sense of what they are reading, and find ways to explain its purpose.

For my Maths and Science boys – literature becomes a literal puzzle, one that they can define, measure, and explain with more ease.

For my Maths and Science boys – literature becomes a literal puzzle, one that they can define, measure, and explain with more ease.

I hope these hints and tips will help you make 19th century literature come alive in your classroom. If you are interested in my resources to help deliver these ideas in your classroom please see the links below!

Developing close analysis skills when teaching literature texts can be tricky. Think of all the things a student needs to know first:

Here’s what we talk through first – explicit and implicit information. I introduce this very simply. Explicit information is clearly written in the text. “Last weekend, it rained a lot.” The text states it rained, so we know it rained. Implicit information needs a little detective work – we use our existing knowledge of the world around us to work out what is being suggested.

We look at the above example. The explicit information is that two people (named Mark and Clara) paid for some tickets for ‘something’ and after that they went to buy some popcorn. We use our existing knowledge of the world to workout that Mark and Clara at the cinema. They could be at a show, the theatre, or at a gig, but we suspect not. And I ask students to explain why not.

Here’s what they generally come up with: most people who go out, go to the cinema (after all tickets for shows, theatre and gigs are expense). If you are going to a gig, you won’t be buying popcorn. This is also probably true for theatres and shows – we leave this for the interval.

After working through this inference together – students try the following:

This week I have also been using this amazing trailer from Miss Peregine’s Home for Peculiar Children. There is so much that is hinted at this trailer – it’s great to discuss.

So now we develop our inference skills into analysis skills!

I first came across the idea of Rainbow Analysis on Twitter about a year ago. You can see the details here.

It is a structured and visual way to ensure that students are creating detailed inferences and then turning this into close analysis. As you can see the sheet has 7 circles in an arc shape. You can pretty much use these circles for any purpose that suits your outcome.

Here is what I include:

Circle 1: quotation

Circle 2: what does the quote mean in your own words?

Circle 3: choose one word (or short phrase) from the quotation and identify the technique used by the author (eg simile)

Circle 4: Now zoom in on the implied meaning of the word or phrase and explain what is suggested by it.

Circle 5: Are there alternative interpretations that could be made of the quotation? Does it contain ambiguous language or ambiguity of meaning?

Circle 6: How does the quotation link to contextual factors such as the period in history or the author’s biographical context?

Circle 7: How does the quotation challenge or impact the reader’s thinking about the character or situation?

Of course, then we colour it all in – to remind ourselves that we are understanding the shades of meaning. Soooo, friends, would you like to give it a go? Well, signup to my newsletter below and you can download the resources from my FREE resource library.

If you are interested in seeing some of my literature resources in action, find me on Facebook and Instagram. Check out my TpT store and sign up for my newsletter for exclusive material and tips and tricks!

When students first begin studying Shakespeare, we spend most of our time focusing on understanding the language, talking about the characters and events, maybe even discussing the themes. What do we do when our students are capable of going further? What’s the next step in analysis and exploration? Well in answer to that question – I wanted to develop a bit on my last Shakey blogpost – and give you a little freebie to help.

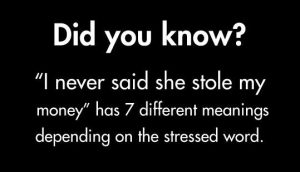

My first stop, after we have moved on from comprehension and inference, into analysis is to focus on the Sounds of Shakespeare. His work after all was written to be performed and this element is essential to our understanding of it. It is the performance of his words that allows us to see and to hear the emotion, the performance is where interpretation becomes more fluid, less set. We’ve all seen this FB post:

Despite how easy it would be if the meaning Shakespeare’s words were fixed, they are not, and our most-able students are capable of discussing this.

Often – for me – this discussion of sound begins with the most simple sound patterns: alliteration and assonance. Specifically these patterns were used (like rhyme) as an aid to memory, actors used these sounds to help them memorize their lines. The rhythm created by the use of these patterns enables the words to flow without having to actively or consciously think about what words come next.

As a lesson opener, write the beginning of a nursery rhyme on the board. Now if you teach a diverse bunch of kids, like I do, you will need to choose carefully. (Remind me to tell you about the time I assume all my students had read Goldilocks…) My starter goes something like this:

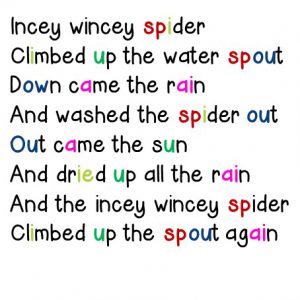

1. Write the words ‘incey wincey spider’ on your whiteboard.

2. Ask the class to dictate the rest. Then ask them when was the last time they actually remember saying this nursery rhyme? I guarantee – even for those with younger siblings – these teens are not going around singing nursery rhymes all day.

3. I then pose the question, why it is easy to remember, when we haven’t said it for years? I often say tell them at this point, that I lived at my old address for 8 years but today I can’t remember my postcode (zip code). Why can I remember this nursery rhyme?

The answer is often because of the rhyming words or repeated words, it is easy to remember. But then we look at little further.

Yes there are a ton of repeated words – and this one reason why I use this particular rhyme, because sometimes one glaring technique (a powerful metaphor or a biblical allusion) can take away from everything else that is going on.

Look at the assonance and alliteration here – the long /i/ sound in ‘spider’ is echoed with ‘dried’ and ‘climbed’; the /ow/ sound in ‘spout’ is seen again in ‘out’ and ‘down’. These assonance echoes aid memory just as much as the rhyming of ‘rain’ and ‘again’. The alliterative elements are also easy to miss ‘spider’ and ‘spout’ – no rhyme, but for purposes of memory it works. I haven’t even highlighted the alliterative /d/ sounds throughout.

Once my students are comfortable with alliteration and assonance BUT before we dive into our Shakespeare play, I use extracts from famous Shakespearean speeches to force their focus onto sounds { see what I did there? force their focus }.

Why don’t I use the play we are currently studying? Well, I could I guess. But the problem is, my students know too much. They know all the characters and themes and once I ask them to start looking at the alliteration and assonance, they are going to get distracted by their knowledge! Wow! I never, ever, thought that would be a bad thing (and it isn’t really). I want them focus on the sounds alone. What do those sounds reveal? Without using prior knowledge, tell me about the sounds.

So download my freebie – right now – and that way you have it all ready to go. You can go through the info pages with your students as much as you like, then pick one of the coloring exercises for your students to complete, including is an extract from R&J and Sonnet 116.

Here students move from looking generally at repeated sound patterns to focusing on specific patterns and what they might mean. There are two explanation sheets included – the yellow one seen in the above picture takes students through the 8 types of alliteration and why they are used. Students can practise identifying alliterative patterns and then giving them meaning. The upside – anything using coloring pencils can’t be real work, right?

Ok. Coloring pencils away now. I am always super impressed with the ideas my students have following these exercises. They create real inferences, real analysis during these tasks. So to keep pushing them on, and building their confidence, we then move onto a simple annotation and exploration exercise.

Annotating a shorter passage (from Macbeth or Henry V) for alliteration, assonance and how these reveal emotion. These sheets give students an opportunity to develop their analysis and write up their ideas but in a low-pressure, low-stakes table. It again generates and aids great discussion.

Analyzing a whole speech – so if you are studying a Shakespeare play, then this would be the opportunity to introduce a speech or soliloquy from that play. For example – when teaching Macbeth, I might pre-teach these skills on the lead up to analyzing “Is this a dagger?” in Act 2, or with Antony and Cleopatra, I often use this as preparation for Enobarbus’ barge speech.

I’ve included part of Mark Antony’s funeral speech from Julius Caesar, as an example for you, partly because this is the first play we teach when our students arrive in Year 7 / Grade 6 at our school. I love the play and by this point in the play (three Acts in) my students are pretty confident with understanding the language and ideas.

So start with a tiny, plucky spider and finish with some fierce and confident analysis.

Teach on my friends.

Do sign up for my newsletter, you will gain access to my free resource library – I have put the answer keys for Sounds of Shakespeare on there, and much, much more!

I don’t know about you but there are some Shakespeare plays that I just love to teach. Macbeth, Antony and Cleopatra, and Hamlet all fall into that category. From start to finish my students and I are hooked on these stories. There also some plays that the kids love more than me – Romeo and Juliet. Don’t get me wrong, I cry every time, but there’s always something missing for me about R&J. I think it might be the lack of justice. It’s just all so damned unfair at the end.

And then there are some plays that I love for the sheer wonder and technical mastery displayed by this Colossus of the writing world. The Tempest is that play.

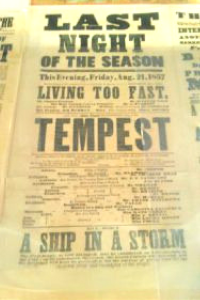

Before I tell you about what a humdinger of play The Tempest is, I want to share this golden nugget with you. Last summer I was honored to spend some time in the Shakespeare archive at Stratford Upon Avon. Amongst other wonders I came across this wonderful playbill for a production of The Tempest from 1857, isn’t is amazing?

I said above that I love The Tempest for its technical mastery and although this is very true (in terms of high rhetoric The Tempest is genius) I also love it because it is a story of real, honest, dirty, and glorious human experience.

The Tempest takes many of Shakespeare’s conceptual obsessions and transports them and us to Island where we are trapped, and then set free. It is a story of family, of love, of power, of revenge, and of forgiveness.

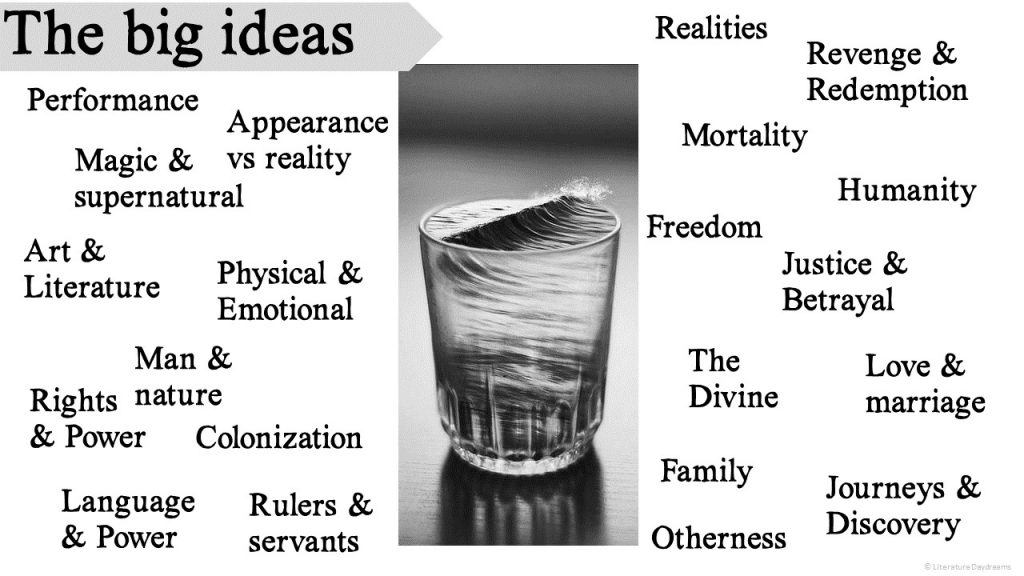

And this is where our analysis of the play begins – with the big ideas:

If you take The Tempest out beyond its simple revenge narrative it is a tale of voyage and discovery, one in which some are subjugated and some are overlords. One where those who have power, will fight to keep it. It is a narrative of colonialism and how the wilderness and its savage inhabitants need civilizing.

Here The Tempest connects with the modern world. And often this is where my students gain their greatest enjoyment of the text, as we consider:

It’s funny, we never have to have the discussion about the ‘relevance of Shakespeare’ because with issues like this, there is no challenging that Shakespeare’s voice is timeless.

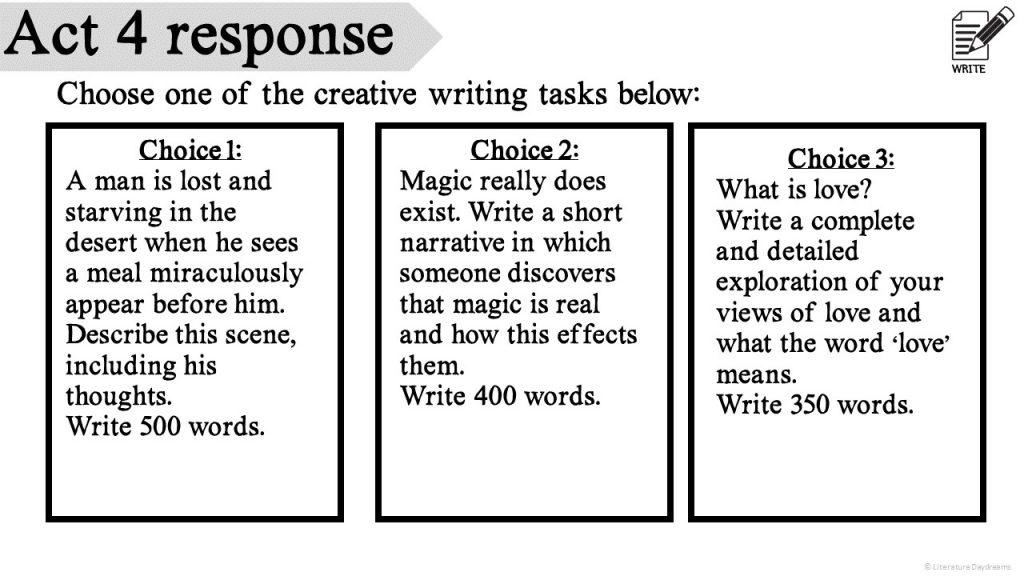

Our class discussions inevitability require some form of written response. When teens set the world to rights, their ideas need to be kept for prosperity. Our focus in here London at the moment is analytical essay writing (and I’ll get onto that in a moment) but there is a strong argument for allowing students the opportunity to explore their thinking in a more creative mode of writing first. We read like a writer, write like a reader, and then analyze like a reading writer.

For me one of the utter joys of teaching Shakespeare is the confidence students gain in analyzing and interpreting his language. Here in London, our students take public examinations on Shakespeare at the age of 16 and at 18. In these exams they are required to write an essay where they dig deeply into Shakespeare’s language and form. As much as I would like to, it isn’t enough to spend all our time talking ideas. We have to roll up our sleeves and get stuck into the words and rhythms on the page.

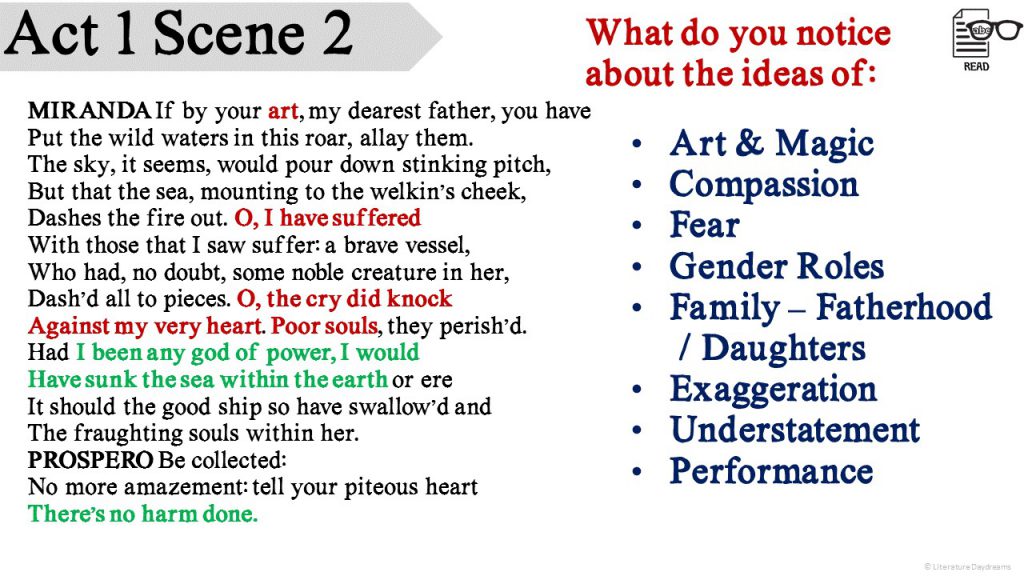

Well, of course, I begin with the ideas in the play. We start out looking for evidence of the key themes and concepts in Shakespeare’s writing. Then we discuss their relevance at that moment, for that character.

We might create a detailed close analysis of this speech looking at:

By starting looking for these universal ideas, students are distracted from the complexity of the language and begin to create analyses and inferences without even realising it. So how do I take their analysis to another level?

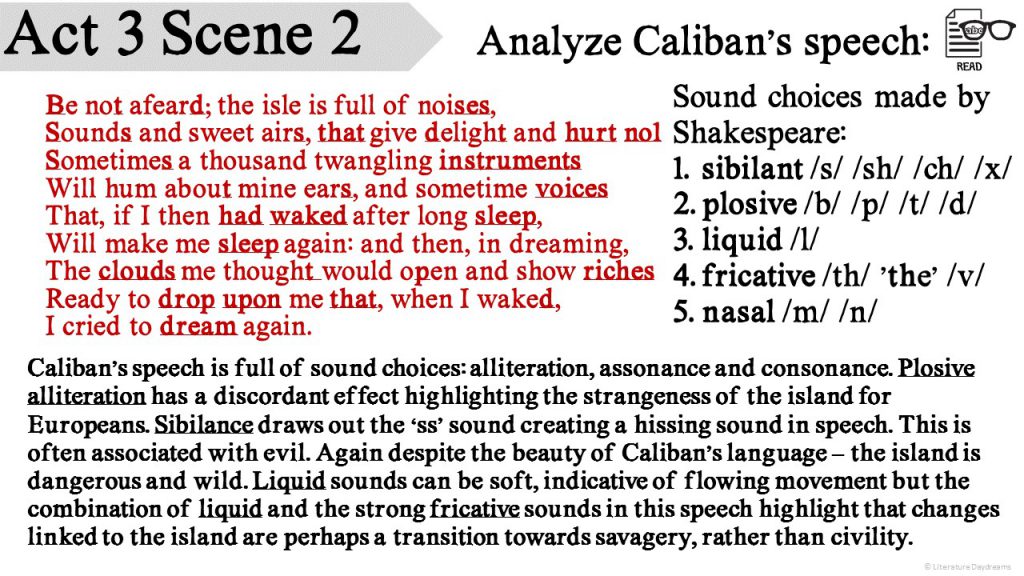

We use Shakespeare to teach a number of complex literary and rhetorical devices, he is well known for his use of rhetorical repetitions (anaphora, anadiplosis, epistrophe). Here students begin to unravel the effect that each of these has. We study alliterative repetitions, the effect of caesura and enjambment, antithesis, and any number of techniques. If you would like some help with teaching the Sounds of Shakespeare – then check my blog post here!

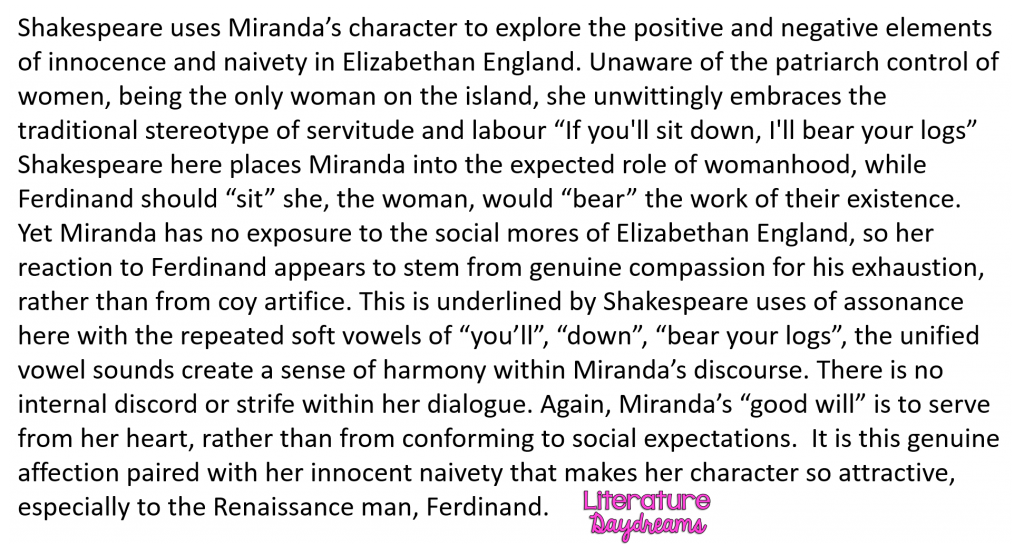

For us, it is essential that students can identify and explain the purpose of each of these. The example essay paragraph below shows the depth of understanding and engagement with ideas, character, language, and technique demonstrated by our students. It’s pretty awesome!

I know! I get it. That was a little bit too much. Do you ever have a phrase that you use with kids and for some reason they latch onto it and use it again, and again, and again? Well, “the social mores of Elizabethan England” became that phrase for me!

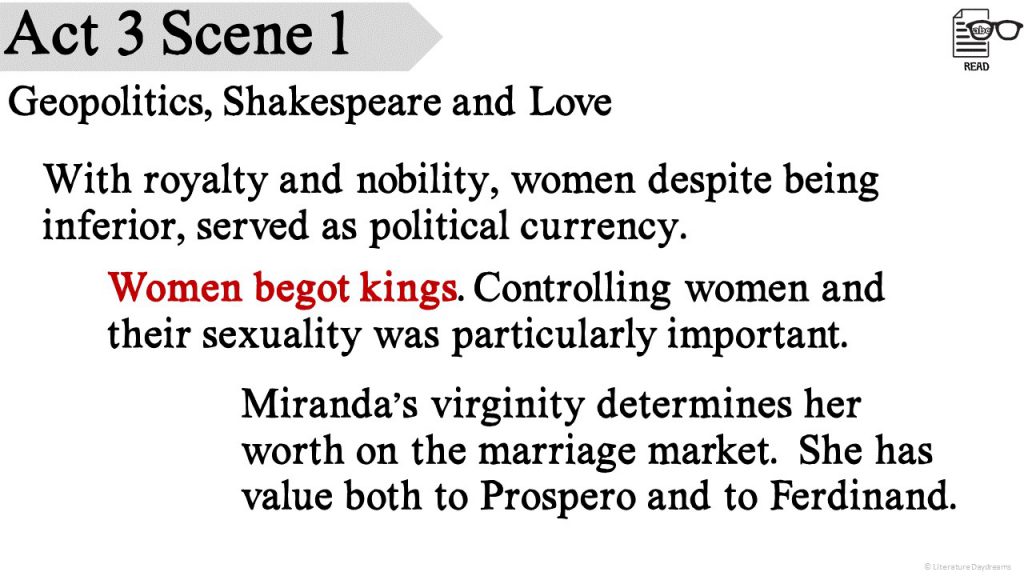

Here’s why, the final and almost the most important thing we do when studying Shakespeare is to place the text within its moment in history. And I don’t mean vaguely “people in Elizabethan times didn’t wash and that’s why Shakespeare makes jokes about people smelling”.

I mean with deep, detailed and in-depth knowledge of the era. The whos, the hows, the wheres and the whens.

Again how can any kid argue that history is boring and irrelevant when my starter question says:

Welll, my friends, I’m glad you asked. Here’s one gem we cover, it quite a lot of awkward detail!

And it’s not just this – we study Elizabeth I and how she was both an awesome and unpredictable monarch. The unity and instability created by a unmarried woman on the throne catapults England into the gender dialogue of the day. James I unifies England and Scotland – or does he/ – returning the ‘small and brutish’ (Thomas Hobbes) nation to rule by absolute monarchy. Add to this the Gunpowder plot, the Age of Discovery, the Inquisitions and Jesuit Equivocators, the age of Shakespeare was rife with political intrigue and conspiracy.

Read, act, enjoy Shakespeare but don’t be afraid to study it. For us, going way beyond the ordinary is what makes us love him.

If you would love to teach The Tempest using the resources I have included above (plus over 200 pages of other goodies) then you can find them all at my TpT store here. You can also see all my Shakespeare resources here. Annnd if you would like – sign up to my newsletter to catch more of my Shakey blogposts!