Category Archives for "British Literature"

[print-me]

[print-me]

Reading literature is a huge part of English and ELA lesson time. Whether you are reading articles, short stories, or studying Shakespeare – it can be difficult often to find tasks that have the ability to engage and challenge students. I was finding that I was setting the same boring worksheets again and again. Fill out a table. Answer these quiz questions. While these are all fine. I wanted something more for my students. That is why I decided to create a set of task cards just for my literature texts.

Very simply these are a set of printable task cards with activities on that students can complete independently or in groups. All I had to do was print them once, in colour, and laminate them. Now I can take them out 4 – 5 times a week and use them with different classes.

The cards I created (and there is a free download here) are based on Blooms’ Taxonomy. There was no particular reason behind this, other than that I wanted to cover a range of skills. Some people treat Blooms’ like it is a hierarchy.

I didn’t want the task cards to be like that. Each of the tasks, I created 60 in total, are designed to get my students thinking. None is better than another.

Interested in downloading 10 tasks cards to try for free? Just click here!

If you love this activity – then sign up for my weekly “Making Sense on Sunday” email where I share two teaching ideas each week that you can use in your classroom straight away!

Sign up below to receive regular emails from me jammed packed with ELA teaching tips, tricks and free resources. Also access my free resource library!

If you teach English or ELA, then you have probably heard of blackout poetry and blackout art. You might have even used this activity with your classes. Here is my take on blackout art -with a twist! You can use it with any literature text you are studying.

I wanted to find something new to do with those book-page scraps knocking about my classroom. So I decided to adjust the blackout poetry concept to fit studying literature. This activity is designed to be used after having read a little way into the novel or play because students will need to have a few things to say about the events, characters, or ideas.

If you are looking for other fun and engaging activities to use in your ELA classroom, why not check out these blog posts:

Also, each week I send an email out to my teacher-friends, in this message, I include one classroom activity (like the perfect review game) and one literature activity (like this blackout writing activity). They are always fun, engaging, and designed to create brilliant learning moments for your students. If you would like to receive this weekly email (I send it on a Sunday morning – ready to help stave off those Sunday scaries), then all you need to do is fill out the email sign up below!

Sign up below to receive regular emails from me jammed packed with ELA teaching tips, tricks and free resources. Also access my free resource library!

I have had a visualizer (document camera) in my classroom for a few years. I would use it once in a blue moon. Mostly to show the class something that I couldn’t copy. This year, I was thinking about how I could achieve 2 of my personal classroom targets. It turns out that my visualizer was the key to meeting both targets.

Quite a few of my classes contain groups of middle achievers, who have a tendency to sit in lessons not doing too much. They complete enough work to scrape by. They don’t cause trouble. They don’t answer questions. They are coasting. This year – I was going to change that. No more passive students!

I want to intentionally cut down on using paper in my classroom. As an English teacher, it feels like I do nothing but generate paper. Unfortunately, we have zero technology available, so that wasn’t an answer. I needed to find an alternate solution to the countless worksheets, printed articles, and practice tests I use.

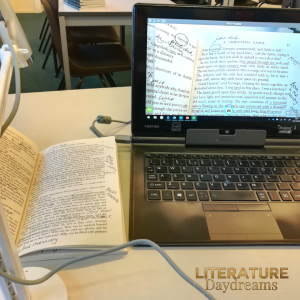

This IPEVO* visualizer/document camera proved to be the unexpected key to my success. My very no-techy explanation of what a visualizer is: it’s a camera, that plugs into your computer USB port and you can manipulate to point at a book, sheet, or whatever on your desk. It then projects the image onto your computer screen and thus onto your classroom screen / interactive whiteboard.

Perhaps you have a visualizer knocking around your department, here are a few ways you can put it to good use. If you don’t own one – I can’t exaggerate enough how much I love mine.

UK link* https://amzn.to/2OorlJh

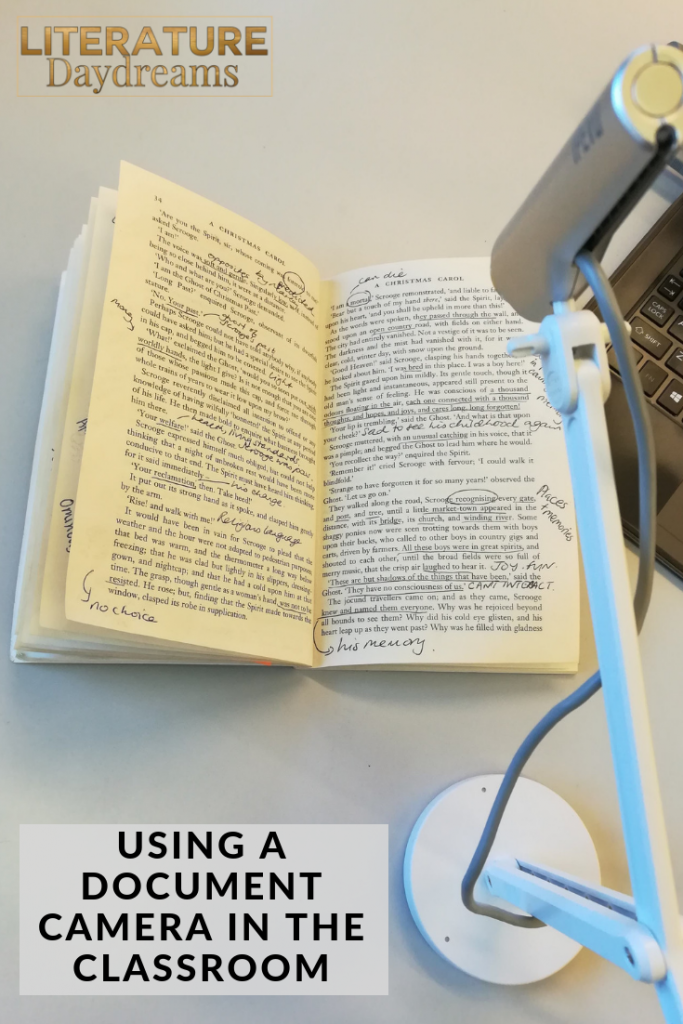

I ‘live annotate’ my literature texts with my class. All my classes have to do examination-style tests on their literature texts. It could be a 19th-century novel, Shakespeare, poetry – they are all tested by a cold extract exam. They don’t get their copy of the book with them. No notes. Just what is in their brain.

So they need a lot in their brains!

First up is ‘live annotation’. I essentially teach the skill of reading and annotating using my visualizer. I put my blank copy of the text under the camera and as we read, we annotate together. It might be comprehension details, word meaning, connotations, themes, or links to historical context.

The unexpected upside for my coasting students was that this activity was so concrete and so easy at the beginning, that they got all the annotations down without even thinking about it. After all, at the beginning, all they were doing was copying.

As time passed, I asked more questions “what should we be annotating here?” and it felt much less like spoon-feeding my students. Everyone was so comfortable by then that they would be suggesting ideas. They had learned a skill which wouldn’t necessarily have come naturally to them!

I can’t tell you how many times I have printed and copied 30 blank table worksheet for my class to fill out. Just because I couldn’t be bothered to go through the hassle of explaining exactly how many columns and rows were needed. I admit it, I was lazy. I couldn’t deal with “I’ve run out of room!” or “It doesn’t fit in my column!”

Now I just use my visualizer to demonstrate exactly what I want the table to look like. I get a blank piece of paper, line it up under my visualizer, draw the first line – everyone copies – draw the next line. It probably takes about the same amount of time as handing out 30 sheets and getting them glued in books.

The secondary upside is my meager contribution to saving the planet by reducing copying!

In addition to my coasting students, I have a few classes that really struggle with English. Although these classes tend to be smaller and specialist, it is always hard for me to get around and spend time with every student.

I use my visualizer as a way to provide me with more 1-2-1 time with certain pupils. Let me give you an example: say we are covering the difference between showing and telling. We complete the first task together, on the visualizer (which means I can also model good handwriting etc). I leave the work on the screen, so my slower writers can take their time to write it down.

I can then circulate around the class to give individual support.

This works better than going through the work verbally because I don’t have to keep repeating myself.

It also works better than typing the work onto my screen / whiteboard because I can interact directly with the ideas – I can circle words, change them, highlight, put stars by things as I am explaining.

I’ve saved the best to last. This idea has made a huge difference to my students progress. I started ‘live marking’ in the same way that I did ‘live annotating’. My classes would complete a piece of creative writing or an essay. I would take responses from 4 – 5 volunteers and mark them live using the visualizer.

Let me break it down for you: say you wanted to work on thesis statements. I would ‘live mark’ those 4 – 5 pieces of work by placing them under the visualizer and looking at just the thesis statements. We would work out together which were the strongest, how to identify the weaknesses, and how to improve any that needed improvement. The rest of the class would then look at their own thesis statements and self-assess.

These are just a few ways that I use a visualizer in my classroom!

Leave a message in the comments if you use a visualizer. I’d love to find even more ways to use it in my classroom!

*These links are affiliate links, you don’t pay any more or any less by using this link. It does mean I get a small commission – which helps keep me in cups of tea!

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eRVm_TAE24A

(Errr – don’t watch this if swearing offends you).

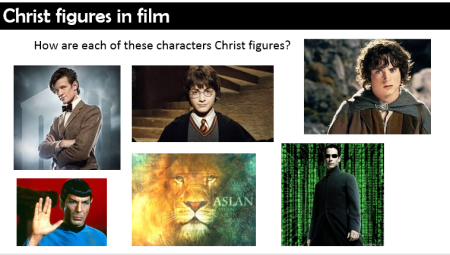

I’m from a very religious family. My step-dad is a former RAF Chaplain (and served in the Falkland Islands) and is now an itinerant vicar (which is not the same as what George and Lennie were); my brother is a vicar. I grew up steeped in religious tradition – from churches were the communion wine is golden to ones where they play guitars and dance. I am enduringly grateful for my upbringing. Not least when it comes to teaching literature. You see – I can spot a biblical allusion at 50 paces.

*The purpose of this introduction is to contextualise some of mild irreverence below.*

Have no clue about the Bible and why should they? Yet, this absence of knowledge results in pupils often struggling to identify and understand many of the deep running threads in literature.

I often describe the need for deep subject knowledge as being like a tapestry – it is complex and interwoven, creating an overarching picture with mini-scenes within. Threads are drawn upon as needed but always remain embedded in and attached to the big picture.

Yet – if this tapestry is English literature – then much of what we study (if not all) was written in a time when religion and religious ideologies were key to moral and ethical outlook, social norms, thoughts on the creation of wealth, and society, and even the nature of life and death itself. Rightly or wrongly identity itself, for much of history, was shaped by religion.

Some may disagree – but I would argue that religion was the predominant ideology of English Literature right up until World War I.

Thus over 700 years of written literature is interwoven into a tapestry where life and religion were twisted threads.

Therefore, to study, understand, and enjoy literature – knowledge of religion and the religious texts, such as the Bible, is essential.

It’s easy, as with all things historical context based, to bolt this knowledge onto a unit of work.

You’re teaching Great Expectations – you paraphrase the parable of the Prodigal Son.

The Lord of the Flies – well, that’s just one big Biblical allusion, although you could just summarise beginning of Genesis and then skip to the New Testament…

The Handmaid’s Tale – same.

Whilst this approach works for individual texts, it doesn’t allow students to develop an overall bank of knowledge that they can rely on. It robs them of the cultural knowledge that is part of our history, as well as our literature.

I like what ED Hirsch has to say in The Dictionary of Cultural Literacy (this is an affiliate link!):

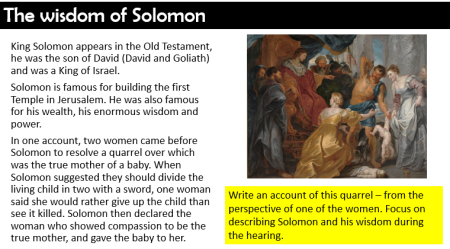

No one in the English-speaking world can be considered literate without a basic knowledge of the Bible. … All educated speakers of American English need to understand what is meant when someone describes a contest as being between David and Goliath, or whether a person who has the “wisdom of Solomon” is wise or foolish, or whether saying “My cup runneth over” means the person feels fortunate or unfortunate. Those who cannot understand such allusions cannot fully participate in literate English.

Religious imagery (both positive and negative) pervades culture still. By only teaching what is needed to tackle one text, we are not weaving the tapestry.

My long-term goal is to create specific units of work that study ‘allusion’ in KS3, knowledge units that study Biblical knowledge as well as mythology from Greek, Roman, English heritage. Not just studying the stories but also studying representations of these stories, characters, and ideas throughout literature.

At the moment, I teach these as explicit, out-of-context starters in year 9. Whilst I am aware this isn’t ideal – I do feel that some knowledge is better than none, for now.

Here’s the list of biblical characters and stories that I teach, with some examples below:

Also because Biblical allusion, among other things, is tested under the AP Literature curriculum – there are loads of fabulous sites that have lists of biblical phrases etc. I like this PDF because it has a bunch of useful literary, biblical and historical allusions.

What to test your knowledge of Biblical reference and allusion? Have a go at this BBC quiz!

Sign up below to receive regular emails from me jammed packed with ELA teaching tips, tricks and free resources. Also access my free resource library!

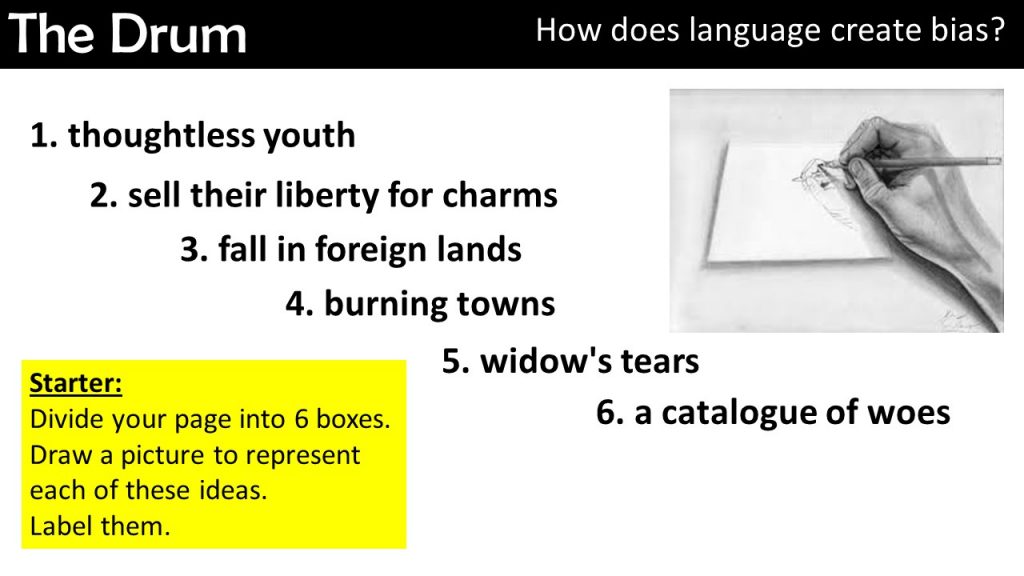

Helping students engage with and understand literature before they read is essential. One way to take the fear away from old-fashioned language or writing that is unfamiliar is to let students play with it before you read.

This pre-reading activity is deceptively simple. Here’s what you do:

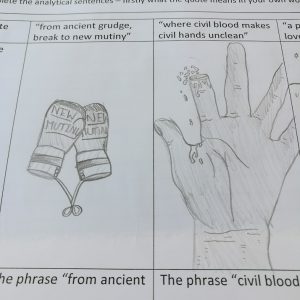

It always amazes me how varied, interesting, and deep my students’ interpretations of these words are. Remember they have no idea what they are going to be reading. Yet students are able to see the depth in the language so much more easily when they only have a handful of words to deal with.

Here are a few examples of my student’s work: from Romeo and Juliet and the task above on The Drum!

If you try using this activity with your class, drop me a note in the comments to let me know how it went! You can see all my Literature resources here.

Sign up below to receive regular emails from me jammed packed with ELA teaching tips, tricks and free resources. Also access my free resource library!

As we get towards September, I know teaching Macbeth is just around the corner. Again. Please don’t misread me, I LOVE teaching Macbeth. It’s almost my favourite Shakespeare play to teach (see my post on teaching The Tempest).

I teach Macbeth every year and every year I find I l-o-v-e it all over again! In my class, there is no room for a quick trot through the play. My students all sit an examination on the play at the end of their 2 year English Literature qualification. We have to know the play and know it very well. Each year I try to add something new to my Macbeth armoury.

Here are 3 ideas that I used this year to take my teaching of Macbeth to the next level!

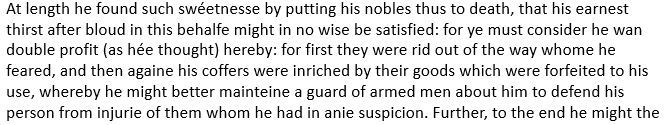

Raphael Holinshed was an English chronicler (similar to a historian today) and it is his chronicle of English history that was Shakespeare’s main source for the play Macbeth. Holinshed published two ‘complete histories of England, Scotland, and Ireland’ in the years 1577 and 1587. Each publication holds a large and comprehensive description of the history of these three nations.

Holinshed’s version of the story of Macbeth describes the reign of King Duncan and shows Macbeth to be a bloody dictator. It also included a woodcut illustration of the three witches that presents them more as nymphs or fairies, and less like the dark, genderless creatures in Shakespeare’s play. You can find out more about Holinshed and his chronicles here at the British Library site.

I have included resources for Holinshed’s history in my Macbeth unit on TpT. If you’re curious about what’s included you can find it here!

How do I use Holinshed in the classroom?

It is very simple, we have a short extract that we read directly from Holinshed (like the one below). We read it directly in Early Modern English (Elizabethan English) – you can talk to students, if you feel like it, about this transition moment in the English language. I love that Holinshed, like Shakespeare, shows both the old styles and new styles in his writing.

So somewhere around the end of Act 4 and the beginning of Act 5, we read a page from Holinshed, describing Macbeth’s later reign (remember Macbeth was actually King of Scotland for 17 years). We chuckle at the funny spelling and words.

Then we talk about the differences between Holinshed’s description of Macbeth and Shakespeare’s one. Holinshed generally comes out the winner because his presentation of Macbeth is bloodthirsty to the extreme.

After that, I ask my students to discuss the play by referencing Holinshed’s history. I might use sentence starters like:

The year that Shakespeare wrote Macbeth was a truly spectacular year for English culture and politics. Not only did London see the first performances of King Lear, Macbeth, and Antony & Cleopatra in that one year but England was rocked, almost constantly by political intrigue.

Let’s start with the obvious:

I have a long post already about how I teach Shakespeare meter and rhythm. You can read it here. I use many of the same strategies when I teach Macbeth, but I can never pass up the opportunity to add a little piece to my metrical teaching.

Here are a few ideas that I love in Macbeth:

If you’re curious to learn more about how to teach the meter and sound patterns in Shakespeare then do read my other blog post and download the free resource.

You can also see my complete Macbeth unit by clicking on the picture below:

Finally if you would like to receive free Literature and Writing teaching ideas straight to your inbox, then sign up below!

Sign up below to receive regular emails from me jammed packed with ELA teaching tips, tricks and free resources. Also access my free resource library!

Teaching language change and development is one of my favorite units. The English language is constantly changing – MTV was fly in the 90s, today it’s the Inbetweeners is sic. What is the link between Generation X’s slang and teaching The Seafarer? Before I begin tackling this Anglo-Saxon poem – I spend some time with my classes looking at language change and the history of spoken language.

I ask students to research words recently added to official dictionaries, sometimes we do this in lessons; sometimes we flip it and this is a pre-unit homework. Always I share a few of my favourites – these were added to the Oxford English Dictionary in 2017

After this, I like to ask students what words they would add to the dictionary, or even to teach the teach a few new words! This is how I learned: sideman, dench, moist (yuck), peak, and would you believe – roadman! Kids don’t get to use these words in my lessons – ever – so this is their one and only chance to sling some lingo.

Then, I ask students to tell me the oldest word they know. They generally come up with something like “thy” or “thou”, occasionally they might throw in something more groovy. Some clever sprite might try “forsooth”.

At this point I introduce Anglo-Saxon words that are still in use today, including Viking, berserk, gun, ransack, hell, troll, saga. Are you sensing a theme? There are some great ones: claw, clip, crawl, get, give, hit, race, run, stammer, and take. The Anglo-Saxons were people of action. Now my class understands that our language is both ancient and very modern.

And so we cycle round to The Seafarer. We begin by writing our own poetic lines based on some of the words in the poem.

We discuss man and nature, adventure and fame, and explore the language of the ancient world. We look at theme, character, and Anglo-Saxon beliefs. We research The Exeter Book and the history of the poem. We create our own poetry, writing, and display work.

If you’re interested in more details about how I teach The Seafarer please click here.

*I send emails with teaching tips, tricks, and free resources to my subscribers regularly. I value your privacy and you can learn more about how I handle your data in our private policy. You can unsubscribe at any time.

Love British Literature?

Access this Austen free resource and a whole lot more!

If you are ready to bring a bit of Brit Lit spark to your classroom - then this Austen resource pack is for you!

If you’ve never heard of the novel Once by Morris Gleitzman then I challenge you to go and read it now. I’ll make it easy – here are the Amazon links! For US readers click here and for UK readers click here (these are affiliate links). Once tells the story of a young Jewish boy named Felix, the year is 1942 and the Nazis have invaded Poland. Felix believes his parents are in danger and sets out across occupied Poland to save them.

We teach Once to our newly arrived secondary students – year 7s – they are aged 11 and 12 years old. It is a fabulous novel for the secondary classroom: short, pacey, with strong characters and unexpected twists. The story is grown-up enough that my newly-minted secondary students are shocked by some of the events. It captures them with a mixture of horror and fascination. We live Felix’s adventures: this young boy speaks our language, we make mistakes and discoveries with him.

We teach Once to our newly arrived secondary students – year 7s – they are aged 11 and 12 years old. It is a fabulous novel for the secondary classroom: short, pacey, with strong characters and unexpected twists. The story is grown-up enough that my newly-minted secondary students are shocked by some of the events. It captures them with a mixture of horror and fascination. We live Felix’s adventures: this young boy speaks our language, we make mistakes and discoveries with him.

For a teacher, Once is the perfect text – I get to dive deep into history and explore why and how the invasion and occupation of Poland became history’s most horrifying genocide. I get to talk about prejudice, racism, violence, and fear with a group of students are just beginning to see the world through growing-up eyes. I get to discuss bravery, courage, kindness, and friendship in the midst of horror, and show our kids that they can be heroes in their own lives.

I cry every time I teach Once. I read it aloud to my students and there are two points in the novel where I outright cry – every single time. I’ve got used to it now. I don’t try and cover it up. I use my reaction – as a mum to the death of a child – to talk about why this fiction-based-on-reality is so wonderful and hard. We talk about why history and truth are important, why stories should be told, and why books are the secret to understanding the world we live in.

Last year I taught Once to a particularly disillusioned group of students. I was hard for me to meet 11 year-olds who already had the cynicism of adults, who thought death was funny, and prejudice acceptable. I just hoped that Felix might reach them. There is a point towards the end of the novel when I show some YouTube clips of Auschwitz and we talk in detail about what happened in the death camps. The following conversation sits in my memory like it was yesterday.

Student: Hold on, miss, is this real?

Me: Real? As in – did this really happen? Is this true? Yes.

Student: What?! Really. This actually happened?

Me: Yes. Between 1939 – 1942 nearly six million people were killed in these camps, that’s about the population of London.

Student: Why didn’t anyone stop it?

Me: Well, it appears that not many people outside knew about these camps. They were discovered once the Nazis were defeated and the Allies were pushing into Germany and Poland.

Student: We really *bleeped* up history back them, didn’t we miss? We can’t let it happen again.

Eighteen months on, I still teach these kids and we often talk about “never again”. What are all the things that we would say “never again” to if we had the chance? Reading Once gave me this opportunity with these kids and I treasure that. Another secret joy for my English teacher self is that Once is the first of a trilogy and I can’t tell you how many of my students scramble to borrow my one precious copy of book two.

If you are looking for a new book to add to your curriculum then Once should definitely be one to consider.

Sign up below to receive regular emails from me jammed packed with ELA teaching tips, tricks and free resources. Also access my free resource library!

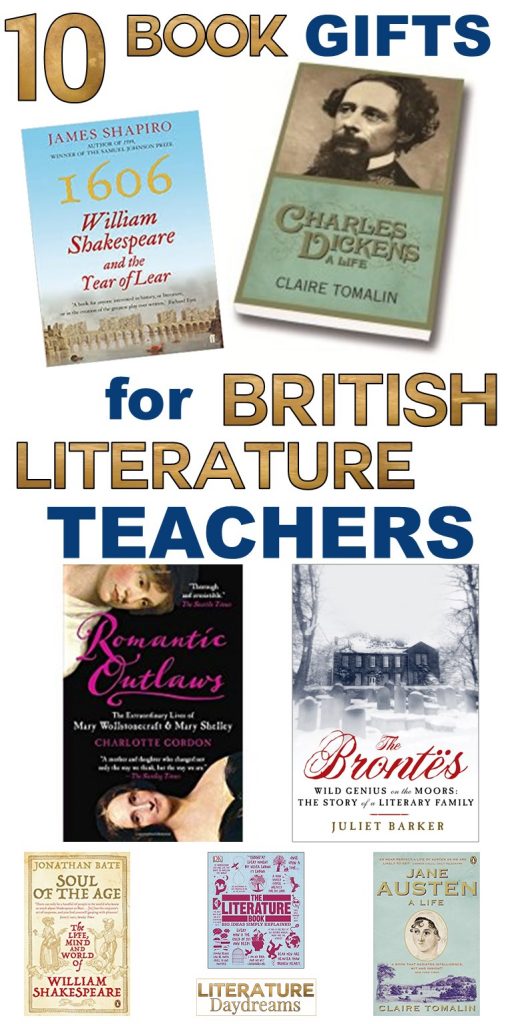

Finding Christmas gifts for high school literature teachers can be tricky – after all, the world is full books – but which ones to choose?! If you are a parent, a colleague, or a family member and you want something special to show your appreciation for a British Literature loving teacher this Christmas, then this gift guide is for you. Below are 10 wonderful books that any Brit Lit loving teacher will adore. I own and have read each one, so these are my personal recommendations. This post does contain affiliate links (and I do receive a small commission from any purchases made using these links) – but I love and use these books myself!

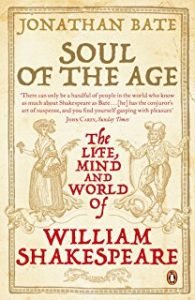

I love this book by Jonathan Bate. He has an easy style but as a Shakespeare scholar – he knows his stuff. This biography digs into the possible motivations for Shakespeare’s many works. It charts his life, education, and adult life – the influence of the politics of the day and how his success changed him. A must-have for any Shakespeare teacher!

I love this book by Jonathan Bate. He has an easy style but as a Shakespeare scholar – he knows his stuff. This biography digs into the possible motivations for Shakespeare’s many works. It charts his life, education, and adult life – the influence of the politics of the day and how his success changed him. A must-have for any Shakespeare teacher!

Click here to see this book on Amazon US.

Or click here to see this book on Amazon UK.

James Shapiro’s book ‘1606 The Year of Lear’ is actually his second account of Shakespeare’s history. This book focussing on 1606 is the sequel to the hugely popular 1599. 1606 was the year that King Lear, Macbeth, and Antony & Cleopatra were first performed – arguably three of Shakespeare’s greatest plays.

I was lucky enough to attend Shapiro’s book launch at the Globe Theatre last year and in about an hour he summarized a thousand minute histories that helped shaped Shakespeare in this year of power. He explores the significance of the shift in politics and power. The gossip about Shakespeare’s family. The struggles in Europe and across the globe. I cannot recommend this account of the history of Shakespeare enough.

Find the US Amazon version here and the UK Amazon version here!

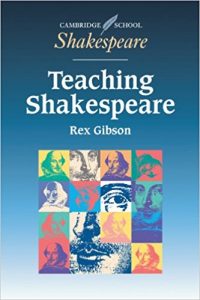

Rex Gibson’s book Teaching Shakespeare is a staple in English classrooms in the UK. It is on the reading list of nearly every teacher training institution for English teachers and this is no coincidence.

Rex Gibson’s book Teaching Shakespeare is a staple in English classrooms in the UK. It is on the reading list of nearly every teacher training institution for English teachers and this is no coincidence.

He has a wonderful way of explaining Shakespeare’s ideas and contexts, as well as giving 100s practical and ready-to-go classroom activities to get students involved in studying, enjoying, performing, and analyzing Shakespeare plays.

Find the Amazon US version and the Amazon UK version here!

This autobiography of Charles Dickens isn’t the only Claire Tomalin book I am recommending today. She is a wonderful researcher and a passionate lover of literature.

This autobiography of Charles Dickens isn’t the only Claire Tomalin book I am recommending today. She is a wonderful researcher and a passionate lover of literature.

I first read this book about 5 years ago when I was teaching Great Expectations and I was trying to understand the shift in Dickens’ narrative style away from social commentary and onto relationships.

Tomalin answered every question I have ever asked about Dickens and many I have not. She sets out his traumatic childhood, his sensational public appearances and acclaim, and the affair that nearly destroyed him. Her writing is joyful and sympathetic and full of wonderful factual detail.

Click here to find the Amazon US edition and then find the Amazon UK edition here.

For me, the title: ;The Bronte’s Wild Genius on the Moors’ says it all. Juliet Barker’s book is a swiping text that fully details their tragically repressed home life and the story of each talented sister. Emily is truly wild, beautiful, strangely unrepressed. Romantic without being a true Romantic. Anne – rejected, alone, unrequited. Then Charlotte, a melancholic teacher, who dreamed of living in her imagined worlds.

For me, the title: ;The Bronte’s Wild Genius on the Moors’ says it all. Juliet Barker’s book is a swiping text that fully details their tragically repressed home life and the story of each talented sister. Emily is truly wild, beautiful, strangely unrepressed. Romantic without being a true Romantic. Anne – rejected, alone, unrequited. Then Charlotte, a melancholic teacher, who dreamed of living in her imagined worlds.

If you are looking for a book that celebrates woman in world that could not and would not celebrate them, then The Brontes is for you.

Click here for the Amazon US version and here for the Amazon UK version!

My second choice from Claire Tomalin is her definitive history of Jane Austen. I always wanted to know why a woman who never married could write with such accuracy about relationships and marriage.

There are so many rumours about Austen (she was engaged for just one evening). Tomalin perfectly captures Austen’s wit, social criticisms, intelligence, and her insight.

I love this book! Find the Amazon US version here. Click here to see the Amazon UK version.

Last but not least is perhaps my favorite of all these Brit Lit novelist biographies – Romantic Outlaws: The Extraordinary Lives of Mary Wollstonecraft & Mary Shelley.

Last but not least is perhaps my favorite of all these Brit Lit novelist biographies – Romantic Outlaws: The Extraordinary Lives of Mary Wollstonecraft & Mary Shelley.

Of course, the lives of Wollstonecraft and Shelley are great fodder for Charlotte Gordon, but her exploration of their truth, their realities, and their impact is extraordinary. The triumphs and heartbreaks of these two women are beautiful articulated – mother and daughter are completely united – in this struggle to find their place in the world.

See the US Amazon version here and the UK Amazon version here!

I can’t seem to leave those Romantics alone! My first reference book is a cross-over history and literature text. Richard Holmes is an expert historian and biographer and in this book he digs into the Romantic era and finds the science, explorations, and inventions that shaped the Romantic imagination.

I can’t seem to leave those Romantics alone! My first reference book is a cross-over history and literature text. Richard Holmes is an expert historian and biographer and in this book he digs into the Romantic era and finds the science, explorations, and inventions that shaped the Romantic imagination.

The full title is ‘The Age of Wonder: How the Romantic Generation Discovered the Beauty and Terror of Science’ and it helps us to see the Romantic sublime experience of the technology of the day.

For any fan of the Romantics or even the Gothic this text is an exceptional grounding in history.

Find the US Amazon edition here and the UK Amazon edition here!

Jonathan Bate makes a reappearance with this amazing introduction to English Literature. If you haven’t seen these “Very Short Introduction” books, they are excellent: short, precise, clear. Enough but not too much!

Jonathan Bate makes a reappearance with this amazing introduction to English Literature. If you haven’t seen these “Very Short Introduction” books, they are excellent: short, precise, clear. Enough but not too much!

If you are studying or teaching English Literature for the first time, then this book is for you. If you are a veteran, this this book will refresh and renew your love of all this Brit Lit.

Click here for the US Amazon version.

Click here for the UK Amazon version.

If like me you love gorgeous visuals and pithy summaries then The Literature Book is for you. A beautiful chronological journey through literature (not just British!) this wonderful book gives a great overview of each literary era and then zooms in on seminal or canonic works.

If like me you love gorgeous visuals and pithy summaries then The Literature Book is for you. A beautiful chronological journey through literature (not just British!) this wonderful book gives a great overview of each literary era and then zooms in on seminal or canonic works.

This book has pride of place in my classroom it is my go-to resource to give historical context, detail, or greater reference to anything we are studying.

Check out this amazing book on Amazon US here and on Amazon UK here.

I hope you enjoyed my gift guide of books for British Literature loving teachers. I would love to hear about any other books that you would recommend – just drop me a comment below.

Thanks for visiting!

Pop Quiz! Which of these best fits you?

If you answered “me, me!” to any of these 4 statements, then today’s blog post is dedicated to you. Here are 3 engaging classroom activities that: give your students a chance to debate; challenge students to stretch classroom knowledge to become real world knowledge; and help them link history and literature with their lives!

It’s easy to forget that Guy Fawkes wasn’t the instigator of the Gunpowder Plot, the man and the money behind it was Robert Catesby. A wealthy farmer and Catholic, Catesby persuaded many of his friends that James I was a weak king and could be easily removed from power.

Guy Fawkes, however, was also not the bumbling fool often portrayed in cartoons. He fought in the Spanish wars against the Dutch Republic and was an experienced soldier.

If you and your students are interested in finding out more about Guy Fawkes and the Gunpowder plot – then check out my Guy Fawkes Hero or Villain resource on TpT.

After you have researched Guy Fawkes in detail, use these debate prompts (a sneak peek from above resource) to spark some deep discussion in your classroom.

**Now a big disclaimer is needed here: V for Vendetta is rated a 15 here in the UK. The whole film is not suitable for classroom use.**

How do I use the film in my lessons to help discuss Guy Fawkes then?

Introduce the story: V for Vendetta (1998) is a graphic novel by Alan Moore. The story is set in a dystopian future where the United Kingdom is ruled over by a neo-facist regime. One night, 5th November, a freedom fighter attempts a revolution. He takes over the national media and makes a speech encouraging all citizens to join him the following year (on 5th November) again to start a rebellion.

Watch the clip:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KKvvOFIHs4k

Read the speech and discuss persuasion:

I have attached a file with V’s revolutionary speech here. We discuss rhetoric and persuasion here and compare it to other political speeches. Then we discuss V’s use of 5th November as a sign of positive revolution.

I pose the questions:

In his dystopian novel, 1984, Orwell writes, “who controls the past, control the future” – we discuss this and the truth of it in our world today.

If your students love V as much as mine do then I often let them watch these two extra clips: The 5th of November Overture and *spoiler* the finale scene (note this contains swears) and will also spoil the film for them – so beware!!

One of the best things about nursery rhymes is that they are all pretty gruesome in nature. If they aren’t warding off the plague, they are accusing you of being a witch. The nursery rhyme written for the ‘celebration’ of failed Gunpowder Plot is just as brutal. We study it for ‘historical accuracy’ and rhetorical techniques and then we create our own Gunpowder Plot nursery rhyme. Sometimes we cast Guy Fawkes as the hero. Sometimes a hapless fool deserted by his comrades. Sometimes we write about James and the Lords in Parliament. Occasionally we imagine the horror if it had succeeded. If all else fails – we create a visualization of the original rhyme with lots of gory detail.

Remember, remember the fifth of November,

Gunpowder treason and plot.

We see no reason

Why gunpowder treason

Should ever be forgot!

Guy Fawkes, guy, t’was his intent

To blow up king and parliament.

Three score barrels were laid below

To prove old England’s overthrow.

By god’s mercy he was catch’d

With a darkened lantern and burning match.

So, holler boys, holler boys, Let the bells ring.

Holler boys, holler boys, God save the king.

And what shall we do with him?

Burn him!

Check out this interactive Guy Fawkes game on the BBC History website. Go to the Powder Plot Game here.

If you wanted to get your students debating; brief history and literature into the real world and challenge your students to really think, then this post was for you.

Sign up below to receive regular emails from me jammed packed with ELA teaching tips, tricks and free resources. Also access my free resource library!