- in British Literature , Classroom , Collaboration , Creativity , Diversity , Freebie Included! , History , Short Films , Teaching tip

Create a BANG this fireworks night in your ELA classroom

Pop Quiz! Which of these best fits you?

- My students love debating.

- I want to push my students to apply their learning to the real world.

- I think we can learn lessons from history.

- My students struggle to link literature to life.

If you answered “me, me!” to any of these 4 statements, then today’s blog post is dedicated to you. Here are 3 engaging classroom activities that: give your students a chance to debate; challenge students to stretch classroom knowledge to become real world knowledge; and help them link history and literature with their lives!

1. Research the man Guy Fawkes

It’s easy to forget that Guy Fawkes wasn’t the instigator of the Gunpowder Plot, the man and the money behind it was Robert Catesby. A wealthy farmer and Catholic, Catesby persuaded many of his friends that James I was a weak king and could be easily removed from power.

Guy Fawkes, however, was also not the bumbling fool often portrayed in cartoons. He fought in the Spanish wars against the Dutch Republic and was an experienced soldier.

If you and your students are interested in finding out more about Guy Fawkes and the Gunpowder plot – then check out my Guy Fawkes Hero or Villain resource on TpT.

After you have researched Guy Fawkes in detail, use these debate prompts (a sneak peek from above resource) to spark some deep discussion in your classroom.

2. Watch and discuss V for Vendetta

**Now a big disclaimer is needed here: V for Vendetta is rated a 15 here in the UK. The whole film is not suitable for classroom use.**

How do I use the film in my lessons to help discuss Guy Fawkes then?

Introduce the story: V for Vendetta (1998) is a graphic novel by Alan Moore. The story is set in a dystopian future where the United Kingdom is ruled over by a neo-facist regime. One night, 5th November, a freedom fighter attempts a revolution. He takes over the national media and makes a speech encouraging all citizens to join him the following year (on 5th November) again to start a rebellion.

Watch the clip:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KKvvOFIHs4k

Read the speech and discuss persuasion:

I have attached a file with V’s revolutionary speech here. We discuss rhetoric and persuasion here and compare it to other political speeches. Then we discuss V’s use of 5th November as a sign of positive revolution.

I pose the questions:

- Is V rewriting history? What is the evidence for your response?

- Can we trust history? Can we trust historical evidence and facts?

- What happens when history is altered or parts of history are forgotten?

- How is history dangerous?

In his dystopian novel, 1984, Orwell writes, “who controls the past, control the future” – we discuss this and the truth of it in our world today.

If your students love V as much as mine do then I often let them watch these two extra clips: The 5th of November Overture and *spoiler* the finale scene (note this contains swears) and will also spoil the film for them – so beware!!

3. Write your own nursery rhyme

One of the best things about nursery rhymes is that they are all pretty gruesome in nature. If they aren’t warding off the plague, they are accusing you of being a witch. The nursery rhyme written for the ‘celebration’ of failed Gunpowder Plot is just as brutal. We study it for ‘historical accuracy’ and rhetorical techniques and then we create our own Gunpowder Plot nursery rhyme. Sometimes we cast Guy Fawkes as the hero. Sometimes a hapless fool deserted by his comrades. Sometimes we write about James and the Lords in Parliament. Occasionally we imagine the horror if it had succeeded. If all else fails – we create a visualization of the original rhyme with lots of gory detail.

Remember, remember the fifth of November,

Gunpowder treason and plot.

We see no reason

Why gunpowder treason

Should ever be forgot!

Guy Fawkes, guy, t’was his intent

To blow up king and parliament.

Three score barrels were laid below

To prove old England’s overthrow.

By god’s mercy he was catch’d

With a darkened lantern and burning match.

So, holler boys, holler boys, Let the bells ring.

Holler boys, holler boys, God save the king.

And what shall we do with him?

Burn him!

An extra sweet treat…

Check out this interactive Guy Fawkes game on the BBC History website. Go to the Powder Plot Game here.

Ok friends

If you wanted to get your students debating; brief history and literature into the real world and challenge your students to really think, then this post was for you.

Subscribe to my weekly teaching tips email!

Sign up below to receive regular emails from me jammed packed with ELA teaching tips, tricks and free resources. Also access my free resource library!

1. Starting at the beginning

1. Starting at the beginning

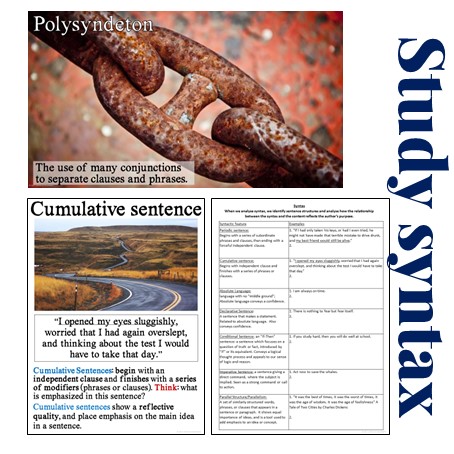

For my Maths and Science boys – literature becomes a literal puzzle, one that they can define, measure, and explain with more ease.

For my Maths and Science boys – literature becomes a literal puzzle, one that they can define, measure, and explain with more ease.