Studying The Handmaid’s Tale in quarantine

Teaching A Level English Literature is one of the real privileges of my job, I absolutely love teaching it – I love the texts, the setup, as well as the discussions and debates I have with my classes.

Then this year everything changed

In late-March when English schools closed for onsite lessons, teachers were thrown into the world of digital learning. For me, this was new and a little scary!

I was faced with teaching half of The Handmaid’s Tale remotely.

How was I going to get my class through the reading?

How were we going to tackle the big questions?

And the small details?

How were we going to debate and discuss the events and ideas?

Too much versus too little

It became apparent early on that, despite my natural tendencies, I needed to give my classes more, extra, above what I would usually, to help them navigate the new and bizarre world of learning at home.

Our A Level Literature classes are truly mixed ability, we accept students with a passion for reading onto the course and don’t worry too much about outcomes on enrolment.

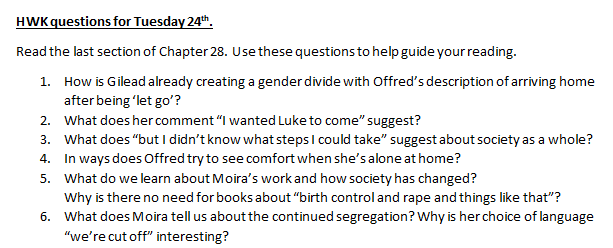

So setting an endless series of questions to guide pupils through reading was not a good idea. You can see here from 24 March (first week of lockdown), my work set could have been overwhelming, especially if it stayed in this form for 3 months. And understandably so.

My students were used to:

Guidance and explanation from an expert

Bouncing ideas off each other and clarifying their own thoughts through dialogue

Adding to each other’s ideas and challenging them

They weren’t used to reading, thinking, and answering in a void.

The fallacy of independence

I just want to pause here and say something about the idea of independence in education. Creating independent learners is seen as something of a panacea in education circles. The constant drive towards independent thinking and independent working can miss the point.

Children need teaching. They are sponges for knowledge and knowledge doesn’t come out of a vacuum.

You might think that The Handmaid’s Tale would be an ‘easy’ text to teach remotely. After all, it’s not laborious 19th-century prose. It deals with contemporary themes. It’s engaging to read.

Well, if you think that, you’d be wrong. There’s a reason why it’s an A-Level text and isn’t because it’s an easy read.

Reading The Handmaid’s Tale requires…

A thorough and wide-ranging knowledge of global history.

A good understanding of post-war social history in America, and in particular an in-depth understanding of Christian Right. This needs to go way beyond a basic understanding of evangelicalism and into how traditional Christianity reshapes individual identity and culture.

Speaking of Christianity – you need a pretty good understanding of Old Testament tradition and writings. Atwood uses the Bible verbatim, she uses passages and alters just a handful of words, she uses passages out of context – all as part of her creation of Gilead’s ideology.

Atwood is a master of language. Her wordplay and multiple layers of meaning created by her words choices and images require careful thought to unpick.

The level of general knowledge needed to interpret the text is enormous (lingerie parties, medicine, the environment, and geopolitics to name just a few). This doesn’t even take into account the numerous details in the Historical Notes.

The novel is full of postmodern strategies, these are tough to explore all by yourself.

Ok, so you get the point. I couldn’t just send work to my class and expect them to get it. No matter how good my questions were.

My school aren’t running live video lessons, for safeguarding reasons (that I completely agree with). I needed a plan that would do more.

So here’s what I did

1) Have fun

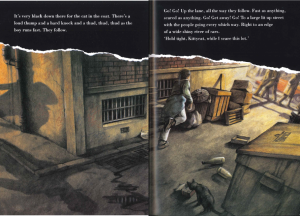

First up – fun, yes they are A-Level students. But they are also kids. So we decided that having fun during lockdown was totally acceptable. Here is my contribution to our Loo Roll Literature challenge

2) Stay normal

If we were studying The Handmaid’s Tale in normal times, we would have been reading the novel and talking about it during lessons.

So that’s what we’ve been doing.

I made videos of me reading and discussing the language and context which I asked my class to watch. I got better as time went on – but at first, I was super uncool at it. Lolz.

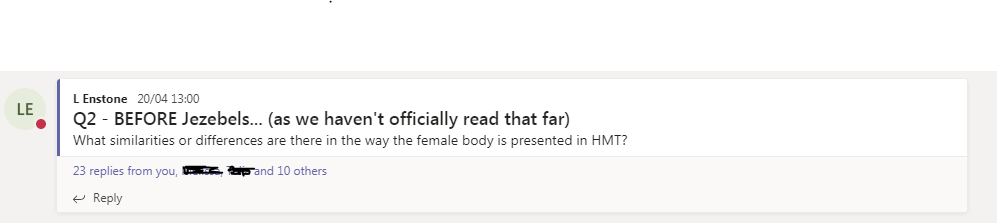

Then we discussed each chapter using the chat function in Microsoft Teams. I would write 5/6 discussion questions for each chapter and would stick them on Teams. We worked asynchronously, so my class just added their comments to the question threads when they had time.

3) Fill in the gaps

Some areas need further discussion and explanation. So this is what I did.

Not only are these useful for my students as they study, but these lessons are now there forever. They can come back to them as they revise. I can use them again in the future.

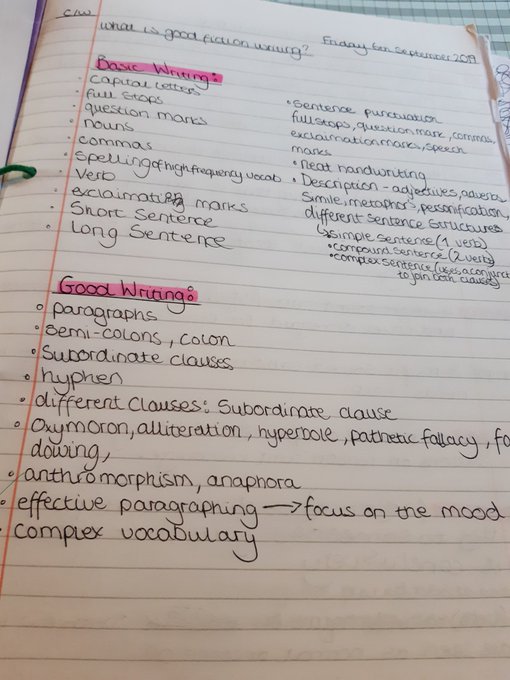

4) Set guided independent study

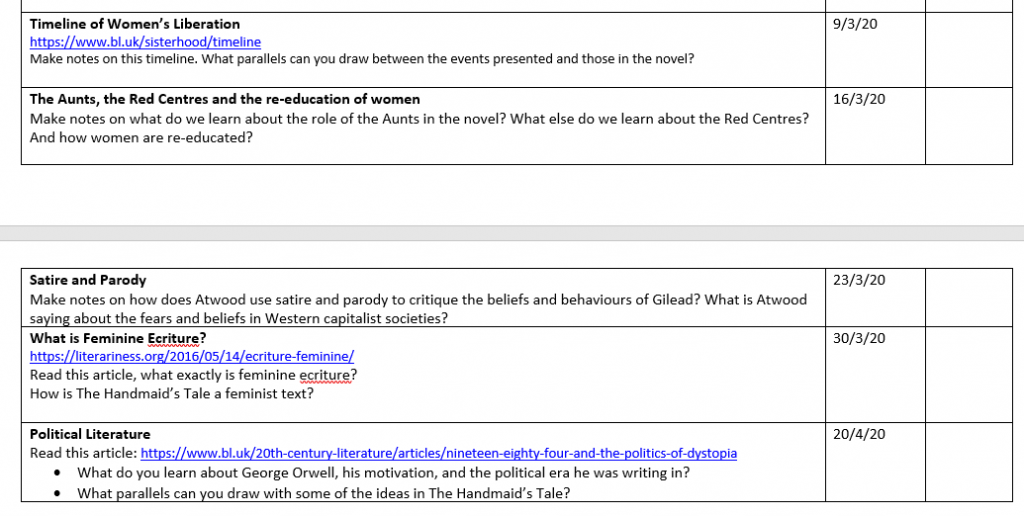

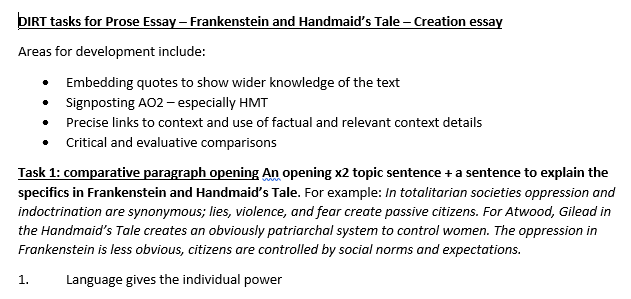

I know I said independence isn’t the only end goal, but that not to say that we should help students make steps towards it. We set independent study tasks each week. They are clear, focussed, and have a defined outcome. This is far more effective than asking students to “read a chapter of the novel and make notes on it”.

5) Don’t forget academic writing

Teaching academic essay writing when pupils are sitting in front of you is difficult. How much help is too much at A-Level? Some students need carefully differentiated support for essay writing. Some arrive in our classroom with their academic voice fully developed.

So I took a one-size-fits-plus approach. Whole class input on essay planning and writing. Then lots of personal, 1-2-1 feedback and advice on essay plans, introductions, etc.

My students are now writing their comparative essays and I hope they feel as confident as they would in my classroom.

Next week move onto the coursework unit and interestingly, independence is the name of the game.